I’ve just watched someone in all seriousness tell a fairly large following that you can use Google Earth to plan a hike and therefore I need to announce categorically that no, you cannot! And thus here is how to plan a hike..

This is about the route, by the way. It’s not about equipment, experience, weather, navigation or any of the thousand other things you’ll need to take into consideration when you’re planning your hike – it’s literally about how to choose and follow a route.

How not to plan a route

“A hike” in this context means something that’s not following roads or clearly marked paths. If you want to walk across London, Google Maps will be fine. If you’re heading for Dartmoor or the Cairngorms or the South Downs or North Dorset or anywhere that’s a bit more remote or a bit more rural, where your collapsed body will take longer than thirty seconds for someone to trip over it, that’s what I’m talking about.

By all means, use your phone or GPS. I don’t personally because that’s not what I’ve been taught. I own a GPS but have no idea how to use it. I don’t have faith in my phone’s battery. I’d want it in a waterproof case in case it starts raining. But if you’re going to use something digital, do use something designed for hiking. There are plenty of legitimate apps, starting with Ordnance Survey’s very own one. Do not use Google Maps or Google Earth. They’re not designed with the level of detail you need for this kind of landscape. I’d like to say they’re not up to date enough but as my OS map is dated “2004, with selected changes 2010 and minor changes 2013”, I guess I don’t get to criticise Google. But those kind of maps don’t show bridleways and pathways properly, they don’t show marshes or access land or shooting ranges clearly enough. They don’t have contours to give you any idea of the shape of the land – you might think that’s over-the-top map geekiness but you wait until your nice smooth digital map isn’t showing you the cliff edge you’ve just walked over, or hopefully only planned to walk over. You wait until you’re lost and helpless and mountain rescue are yelling at you for endangering yourself by using a map that’s so utterly inadequate.

There are plenty of places you can download GPS tracks, if you can’t actually follow a map yourself. Do that. I use Wikiloc for uploading my walks. I’ve heard a lot about Komoot and Alltrails. You can google “walks in [area]” and that’ll probably give you pages about walks people have done with GPS tracks. But I really can’t advise strongly enough finding a professional to teach you how to use a paper map. Then a whole world of walking and planning and adventure opens up before your very eyes.

Plan a hike with me

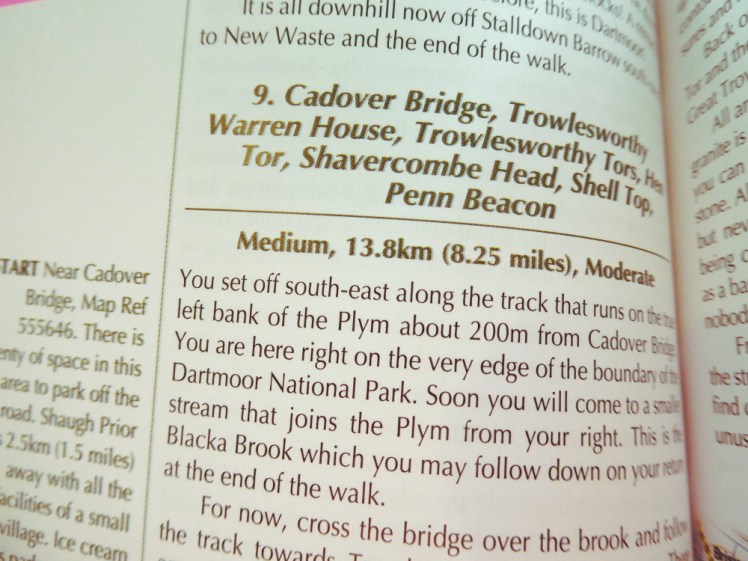

This particular one is going to be on Dartmoor because that’s where I go for a serious hike, it’s an area I know, an area I’m likely to go to in order to use this plan and somewhere that’s serious enough that I do generally feel the need to plan before I go. I’m going to start with two things: my OS map and my walking guidebook. I personally use the Cicerone guide but there will be hundreds of guidebooks out there. Try to pick one that gives you a decent map. I’m not actually keen on the Cicerone maps – they’re too small without enough context and the routes are drawn on in lines that would be a couple of hundred metres wide if translated to the ground. That’s a lot of margin for error.

Decide on the area of your walk

Obviously first there’s your region. I pick Dartmoor for hiking because I’m very slowly going after my Level 2 walking qualification and Dartmoor is the closest area to me that has Level 2 terrain. That’s not going to be relevant to you. Pick your area, whether it’s a big open national park or just a bit of tamer countryside. Don’t go too big too soon. That you’re reading how to plan a hike says to me that you’re not ready for an expedition across the Scottish Highlands, for example.

Next, zoom in. Dartmoor is big. The Lake District is huge, the Cairngorms are colossal. If you’re trying to plan a hike just generally in that area, you’ve got a lot to play with.

To zoom in myself, I’m going for somewhere around the west side of Dartmoor because I’m camping between Okehampton and Tavistock and have my own car. You might be limited to somewhere accessible by public transport or you might want somewhere more or less hilly or more or less remote. Have a think about an approximate area according to your own parameters and narrow down the location of your walk to at least “somewhere around the west of Dartmoor”, “somewhere in the vicinity of my favourite hill”, “somewhere I can see this lake” etc.

Look through the guidebook, if you’re using one

When I do my walking weekends with the region ladies, we don’t use a guidebook. But it’s a useful thing to do, especially if you’re new to route planning. You know you’re almost certainly going to get a walkable walk, that someone else has walked and has confirmed exists.

All we’re going to do is look through the guidebook and find something that fits the parameters of the walk I’d like to take. Easy-peasy. Possibly unnecessary to detail it as much as I’m about to.

My guidebook has a map in the front showing the numbered walks. I take a note of all the numbers that are within roughly the area I’m looking at. Today that’s 34-41 and 9-18, the ones on the western side of Dartmoor.

Now look through the book at those walks. That’s easy in this book: there’s a summary in the back. I’m marking the table on the left-hand side because all the information that’s relevant is on the right-hand side and I find it easier to run down one side than keep reading all the way across the table.

For my logbook walks, I need walks at least 10km long so I’ve circled all those. I’ve also marked them M, H and VH according to the difficulty column. So now I’ve got my walk number, my distance and my difficulty all right together in the same place. In the 34-41 bracket mentioned above, I can see that 39-41 aren’t long enough for my needs. I’ve ticked number 35 because I’ve already done it. And I’m going to feel lazy so I’m not up for a hard or very hard walk – and besides, I’ve read the description of 36 enough times to know that it’s going to test my navigation skills enough that I’d rather not do that one alone. In that group, that leaves me 34, 37 and 38.

In the 9-18 bracket, I can see that several aren’t long enough and that I’ve already done one. That leaves me 9, 10 and 19. See, I’ve already narrowed it down to six walks. 34, 37, 38, 9, 10 and 19.

I did a routecard for 37 last time I went to Dartmoor and discovered that it starts with two solid hours of climbing. Nope, cross that one off. 38 I’ve mislabeled as medium when it’s actually hard so cross that one off too. 34 doesn’t excite me. 19 is also actually hard rather than medium so cross that one off too. So of the ones that fit all my criteria and that I haven’t crossed off for various reasons, that leaves me 9 and 10. And then because 9 is the shorter one and I’m feeling lazy, as I said, I’m opting for that.

See, you’ve picked a hike! That’s all you need to do, really. The guidebook will explain where to go and what to see and you’ve got a map to follow. I personally would make a route card but that’s because this book rambles and it’s so much easier to just follow my route card than to try to pick out the route from “oh look, there’s a quarry and here’s an anecdote about it and we’ll tell you where to go next in two pages’ time”. Another thing about a routecard is that you can slip it into your map case or your pocket and you don’t mind if it gets damp, whereas I’d mind my guidebook getting wet.

I’d also follow the route around on my map beforehand to see if anything pops up that’s a surprise. This walk is a round walk from Cadover Bridge out to an unnamed summit between Langcombe Hill and Shell Top which involves quite a bit of walking across open moor. I try to plan my walks to follow footpaths or bridleways or boundary lines, or something that suggests anything other than picking my way through waist-deep gorse or heather. As this is a walk in a well-known book, I assume it’s fine but it’s not something I would have picked from my map. This is why we use the map.

Look at the map

So that’s one way of planning a walk. Now for another.

Today we don’t have a guidebook and we’re going to use the map to create a route. This takes more effort, not least because I’m going to have to measure the finished result to make sure it’s long enough for my needs. I’m going to pick the north, near Okehampton but east of the Okehampton ranges. They’re perfectly safe when they’re open but I’m going to want to double, triple and quadruple check that because I do not want to get shot. There’s a nice big area of open moorland up there. I’ve picked this area because 1) it’s near when I’m staying 2) it’s a nice big open access area 3) it’s not within the danger area 4) it has paths and landmarks 5) it looks doable.

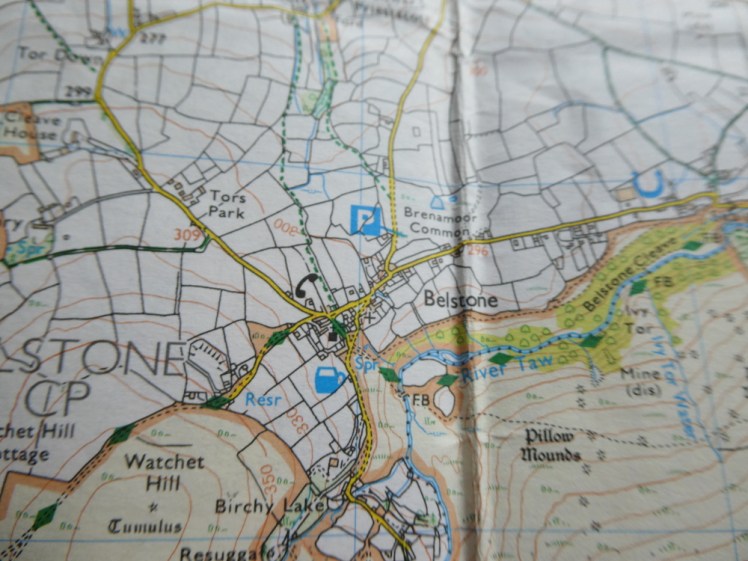

I fold my map so it’s two sections wide because that’s all the room I’ve got on my desk and then I examine it.

First, where to park? Dartmoor is littered with parking places but none of them are marked in this area on my map. Where is there a car park? Aha, Brenamoor Common. That’ll do then. I’ve already done “how to write a route card” so pop over there but in short, I’m going to write the coordinates of the car park at Brenamoor Common on my route card. Yes, you’re going to want to write a route card for planning a route like this. If you leave it in your memory, you’ll forget it. You’re also going to want to know the length and time and amount of climb. I’ve written route cards before and gone “oh no, that’s far too long and far too steep, forget that!”. I’ve also been on walks where someone else has the route card and it’s a lot more fun if you can look at the map at any point and know where the walk is going, rather than blindly following someone else across bleak moorland or mountain.

Where can I go from that parking space? Well, there’s a nice yellow road that leads to the open access area. Yellow, according to the key, is “a road generally less than 4m wide”. By Dartmoor standards, that’s a main road but it’s going through a village so it’ll probably have a pavement and a speed limit so that’s fine.

Now I’m on the open access land and there’s a world of possibilities before me. In this case, there’s a path of some kind marked from that corner so I reckon I’ll start by following that. It leads me across and back into farmland, towns and villages and I don’t want that, so I’m going to turn south at some point and into the expanse of moorland.

There’s a big hill about two kilometres south of that footpath. It’s ringed by a big green path. On my map, green is a public right of way and this is a bridleway. So I’m going to cut across the moor to join the bridleway. There’s a watercourse between the two but it does say disused so I’m going to take a chance on it being possible to get across.

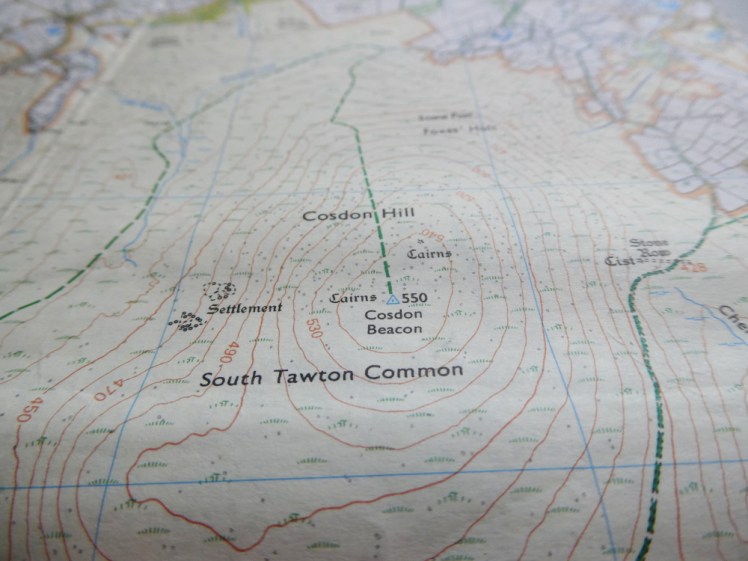

From the bridleway there’s another bridleway that leads to the summit of the big hill. I think climbing up would be a great idea. Probably a good stop for lunch. Maybe an early lunch. Contour lines says it’s a pretty big climb – from the first bridleway it’s 150m up. That’s 10-15 minutes extra time on my route card just for climbing, not to mention the approximately half-hour I’d allocate for the kilometre and a half. However, I know from previous experience that 3km/h is an average speed and however impossible it feels to climb a hill while I’m doing it, on the occasions when I’ve timed it to compare to my route card, I actually do it much more quickly.

Then it’s about another kilometre and a half across to Little Hound Tor. Most of that is downhill, with just a little summit at the end. Where do I go from here? I could carry on in that line and follow the path to Hound Tor – not the famous Hound Tor, a different one, but as it gets a bit bare from hereon in, and I need to get back north eventually without going either into a gorge or into the danger area, I’m not going to bother.

There’s a settlement just a little west of north from Little Hound Tor, via the bridleway. Well, that looks good. If it turns out my route is short when I get to the end, I’ll pop out to big Hound Tor and back just to extend my walk to its necessary length and bag another tor, but that’s an optional extra once the routecard is written.

From White Hill I could follow the bridleway back, rejoin the footpath and walk back into Belstone and my car but that’s not very exciting. There’s two fords off to the west joined by a path of some kind. But getting to the south ones appears to involve wading through Taw Marsh and Dartmoor marshes are unpleasant things so forget that idea. Ok, I’ll follow the bridleway north until I’m more or less level with Cosdon Beacon and then strike downhill to the ford.

From the other side of the ford there’s a footpath of some kind heading north. I’ll follow it to the foot of Belstone Tor and then pop up there. It’s a bit steep – 110m in less than half a kilometre. Route card says 21 minutes but as I said, it’ll probably be quicker in reality. Then I see no reason not to go down the other side and join the path by the cairn circle. Then I can follow the path north until it joins what I think is the Tarka Trail, which I’ll follow back to Belstone and the car. Actually, I might pop across to Scarey Tor. It has a great name and it’s only just over 500m in total detour and only an extra 20m climb. Seems silly to miss it out, especially if my route comes up short.

I’ve now written out my route card and it comes to 10.7km. I’ve included a 30 minute lunch break at Little Hound Tor and a 10 minute rest on top of Belstone Tor and that takes me to 5 hours and 6 minutes. My magic route card has a time column too, so starting at 10.30am, I get back to the car at 3.35pm. See, this is why you need to make a route card, these kind of details can be important. Imagine planning a route and discovering that you’re not going to finish until well after it gets dark. That’s something you want to plan for – unless you’re deliberately going out for a night hike or night practice or something and you know it’ll be planned and safe, don’t get caught out in the wilderness after dark.

So that’s roughly the process. Look for paths, look for landmarks and see if it looks plausible to join them up. If it doesn’t, as in the case of my marsh, find an alternative.

Here’s the route card for that walk we’ve just planned, by the way.

Be prepared for your plan to fail

Paths on the map don’t always appear on the landscape and paths on the landscape aren’t always marked on the map. The map therefore can only give you an idea of what you’re going to experience. You always have to be ready to abandon your plan and make a new one, which is why an ability to use your map and compass is invaluable – you have to be ready to say “ok, it turns out I can’t actually go there, so I need to go there and that means I’m going to have to figure out and follow a way”.

In the case of this route, I can always give up and just follow the bridleway back. Getting back alive is more important than getting my 10km logbook walk and changing plans according to conditions is a valuable skill in itself, so you’ve just picked up a good bit of experience, even if it’s not one that goes in the logbook. Take a look at your route and make sure you’ve got options in case of unexpected marshes or missing bridges or even just bad weather. You have to be prepared to abandon your hike if the weather is truly inclement. I don’t mean that you can’t walk in the drizzle, I mean that a mist somewhere like Dartmoor can be fatal. Zero visibility makes navigation on moorland or mountain virtually impossible. I know a group of ladies who would barely blink at zero visibility but they’ve been trained mountain leaders for fifty-odd years. You and I do not have those skills. Know when to call it a day. Mountain rescue will thank you.

I know it’s all a lot more complex than just opening Google Earth but honestly, this is the way to get out in the wilds safely. As I said before, I can’t advise strongly enough finding a professional to teach you how to use a paper map and compass and while you’re learning to navigate, you’ll also learn about route planning.