Welcome to the former RAF Tarrant Rushton. I’m not a person who writes a lot about 20th century military history. If I’m writing about history, it’s far more likely to be the 9-11th centuries. I love a bit of Saxon or Viking or Romanesque ecclesiastical architecture. I’ve complained, recently, about the 17th century being too modern. But today we’re coming a long way forward, right up to days still in living memory.

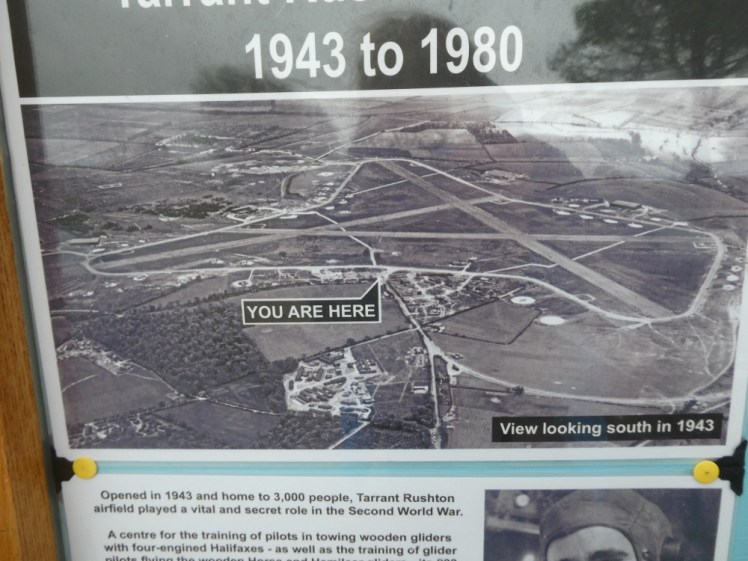

Today, you wouldn’t place the remains of Tarrant Rushton airfield as an important WWII airbase. You wouldn’t think it could have launched the first Allied troops to set foot in France on D Day. You wouldn’t think modern aviation technology was pioneered here. But you’d be mistaken.

The first thing you should see at the former main gate is the memorial and information board. Human eyes and attention being what they are, the first thing you’ll actually see is the hangar. It’s an enormous barn, painted black, big enough to store Halifax bombers in. If you peek through the gaps in the door, you’ll see a collection of farm machinery, mostly tractors of varying ages, and a few vintage buses in varying stages of restoration. But when my grandmother was a teenager, this was a busy RAF base.

The Halifaxes mostly didn’t do too much bombing from here. They did some supply drops and personnel drops across Europe but their main job right here in Tarrant Rushton was towing Horsa and Hamilcar gliders – “single use jobbies”, to quote my dad, as landings were generally not all that well controlled and left the gliders quite a lot less pristine than when they were launched. In fact, the first Allied troops to set foot in France on D Day were launched in gliders from here and the first men to actually stand on French soil had a sufficiently inelegant glider landing that I imagine they were thrown onto that French soil and didn’t in any way “disembark” from their aircraft.

Once there were four hangars around the edge of this airfield but only two survive today. The other survivor is now a sawmill. The old taxiway, or perimeter road – as I said, this isn’t my period – still survives and it’s in reasonably good condition. It’s a public footpath, a sort of squashed misshapen triangle which used to surround three runways. I took my dad for a walk round it because he needs to be walked at least once a week and he’s a Man of a Certain Age and so is interested in the 20th century military history and also in the part-restored vintage buses in the hangar.

We went clockwise around the path, partly to investigate the “Roman villa (site of)” to the immediate east of the airfield and partly to see if you could get a better view of the hangar’s vast interior from its other end. We also took ten minutes to chat to the owner of the buses. He rents four spaces in the hangar and is therefore at the mercy of the farmer who now owns the behemoth but if he had his way, he’d turn one side into a bus museum and the other side into an RAF Tarrant Rushton museum. It’s a good idea – or at least the military half is a good idea – but the farmer’s “not keen”. Of course, it’s where he keeps his tractors, and the conversion would be expensive and it probably wouldn’t be very profitable but then, I’ve never got the impression farming is very profitable either and a museum is a good a diversification as any.

There was no sign of the Roman villa and no sign when I checked Google Maps either. Sometimes from the air you can see a ghost of past structures in the crop – the three runways in the middle of our footpath are very visible on Google Maps. It’s to do with the depth of soil – ruins a few inches or a few feet down dramatically affect plant life above, leaving visible lines of dying or stunted vegetation to mark exactly where something once stood. That’s how they discovered the remains of the villa in the first place. But now, there’s no sign.

There’s no sign of the old Roman Road either. It runs between the airfield and the villa in a perfect straight line to the eastern gate of Badbury Rings, an Iron Age hillfort just a couple of miles away. I’ve visited four hillforts so far this year and one history fact I’ve learnt from it is that Iron Age and the Romans overlapped, even though Iron Age feels like it should have been thousands of years earlier. It’s more than likely Badbury Rings was still occupied when that road was built.

To return to the 20th century, we rejoined the concrete taxiway and continued our walk. The second hangar is on the next stretch and while it’s an enormous black shed easily visible from the first hangar, we hadn’t detected the woodchipping operation from back there. Neither had we realised the airfield is on a surprisingly steep hill. Well, it’s hardly steep, gaining about 25m of height from one end of the 2000 yard runway to the other, but it’s certainly not pancake-flat either. Once we’d realised that, Dad decided it wasn’t such a bad thing. Launch downhill, using gravity for extra speed to take off, land uphill for gravity to help kill speed as you touch down. And that’s why I’m not a pilot, because my instinct would be the other way round for an exciting landing.

We knew the runway was visible from the sky but it’s not from the main gate. Now we discovered why it was visible. It’s still there! The rutted concrete track in existence in 2020 is a fraction of the width of the original wartime runway. I don’t know how big a Halifax bomber is but I can picture “probably a bit bigger than an easyJet plane but with wider straighter wings and four big engines and a tricycle undercarriage”. You could run it down that track, I think, but you’d want to do it pretty carefully and not at speed and definitely not from the air. The remains of the runway were marked at both ends with “private – do not walk here” signs which we can’t quite account for. If the perimeter taxiway is accessible to the public, why isn’t the runway?

The other two runways are long gone, at least from ground level, although we paused at one point when Dad said “So I guess the runway was right here?” and I got out my map to point out that it definitely wasn’t. And yet when we returned to the gate and looked at the old photos on the info board, it pretty much was where one of the shorter runways had been.

After the war, Tarrant Rushton airfield became the property of experimental aviation company Flight Refueling, or Cobham, which is still active in nearby Wimborne, although their main centre of operations is now at Bournemouth Airport, referred to on the info board as “Hurn”, the name still more likely to be used locally for the airport.

Flight Refueling tested, mastered and perfected various… well, refueling techniques from this airfield, by which I mean in-flight refueling. Records have been set here. Of course, post-war civilian aviation pioneering doesn’t tend to capture people’s imagination unless it involves really high speed and what people remember Tarrant Rushton for is three or four years of wartime service rather than thirty-plus years of aviation advancement.

Other than the two hangars, the long straight path across the field and the ghosts on aerial maps, there’s very little sign that this was a busy working airfield right up until 1980. The concrete pulled out of the runways when they demolished everything was repurposed to build the bypasses around Wimborne and Blandford Forum, a small town on its other side, in much the same way Corfe Castle’s stone was used to build Corfe village. Waste not want not. Now the long, straight flat taxiways provide great roads for horseriding, running with your dog and family days out with kids on bikes and scooters. Facilities are limited to one bench on either side of the airfield and a few small blue marker arrows in case you can’t follow a concrete triangle but it was busier than I expected on a grey Saturday during Lockdown 2.0, clearly with people who felt it was a good location for some very well socially distanced outdoor exercise.

Maybe one day they’ll be coming to the RAF museum to see what this place used to look like.

One thought on “A Single Map episode 3: Exploring Tarrant Rushton Airfield”