When you think of Switzerland, you think of chocolate and cheese and skiing. Well, I don’t ski and I covered the cheese in the post-snowshoeing fondue I had in the last post which means it must be time for the chocolate! And it is! Long story short, I took the train out to Switzerland’s oldest chocolate factory, did a factory tour with lots of taste testing and then I did a chocolate workshop.

Maison Cailler was opened in 1898 in Broc, an hour and a half north-east of Lausanne by train – two or three trains, actually, depending on what’s due in next. It claims to be the only chocolate company in Switzerland that uses fresh milk rather than milk powder in its chocolate, which I believe but on the other hand, do they mean Cailler or do they mean company owner Nestlé, the former massive Swiss chocolate maker turned massive multinational conglomerate which went into partnership with Cailler in 1929? Cailler ended up in Broc because it had easy access to plentiful water as well as the rolling hills full of cows and easy access to fresh milk and now it makes a really scenic trip out in itself. Just eight miles away, on the other side of those hills, is the panoramic GoldenPass Express train but if you’re willing to change trains once or twice, you can have a scenic train trip without the tourist premium price tag.

I arrived at Maison Cailler just in time for its 11am factory tour. Because I was only there for the weekend and it was Sunday, I had all my luggage but Cailler has free lockers, as long as you have either a 1 or 2 franc coin, which gets returned to you when you unlock the locker. The obvious ones are right inside the front door but if they’re all occupied, there are more hiding between the cafe and the toilets, so I was able to go in with just the basics in my hands.

The visit

You’re given an audioguide in the language of your choice and for the first twenty minutes, you follow a sequence of doors into a sequence of rooms that walk you through the history of chocolate, from Quetzalcoatl and the Aztec Empire to the arrival of Cortez, to the popularity of chocolate in Europe, to the establishment of Cailler factory and finishing on the buyout by Nestlé. In that little talk, they praised Henri Nestlé as a visionary for inventing baby formula, a subject I would personally have left well alone, given that it’s by far the most controversial thing it’s ever done and people have been boycotting Nestlé for decades over it. Just stick to the chocolate, pretend that the baby formula never existed. In my own defence, I didn’t know Cailler was owned by Nestlé when I booked all this; I naively thought this was a beloved massive but independent Swiss company. I would still have done it – if you’re going to eat chocolate, there is no truly ethical way to do it and in the 21st century, it’s impossible to live life while avoiding the big corporations. Did I say that I myself would have just not brought up the subject and pretended there was only chocolate? Yeah.

Anyway, after this walk-through, you’re released into the chocolate factory. Not the open factory floor, obviously. This is a room with glass walls where you can see some machines clearly just on display and some that are moving around in the background, which might be actually making chocolate. Around the walls are pictures of the chocolate-making process, from the growers to the people who pack the finished bars, via every logistics job and every job in the entire factory. There’s even a little story from one of the cows. There are also four boxes here so you can see what the beans look, smell and taste like. Having stuck one in my mouth and discovered it’s not edible at that stage, I then put it in my pocket so yay, I have a couple of raw cocoa beans! They really do smell strongly of chocolate.

Past that room is a counter where someone is painting chocolate into moulds to show how hollow 3D chocolate shapes are made and then you get to the first fun bit – a tray of little chocolates! These are for tasting right there and then, not for pocketing but that’s fine because after another look at some of the machinery, you’re into the tasting corridor, where you take a little purple chocolate bar and follow the instructions. Or you do if you’re being good and not just hoovering up free chocolate. Look at it. Look at the colour, the shine, the shape. Smell it – how many layers of scent can you detect? Listen to it – does it make a good snap? And finally, taste it. Yeah, finally – that thing is melting all over my fingers by the time I’ve examined it closely. Suck in some air like a wine expert, see how the oxygen makes it taste. And does it have any aftertaste?

When you’ve mastered the art of tasting, you find yourself standing in front of a display of eight different chocolates. I admit to skipping a few of them – I’m not a fan of marzipan or whole nuts and tasting each chocolate properly is very different to shovelling one of each in your mouth as you walk down. Having been nervous about a lemon Lindor ball a few years ago, I was surprised to find the little stripy lemon Cailler chocolates are surprisingly tasty, and so is the noir cremant, which I guess is like the equivalent of Cadbury/Mondelez’s “dark milk”.

Because I’d skipped over a lot of the talking heads, I was out in just under an hour, so I went outside to escape the heat of the factory and to appreciate the snowy scenery. I got an orange juice in the cafe (which came with yet another chocolate) and sat outside. Why am I sitting there when I could just go on to my next adventure? Because my next adventure was nearly an hour and a half away back inside the factory.

The workshop

At just before 1.30pm, I went back in for my chocolate workshop! This is held in a double-height kitchen just behind the reception desk and has glass walls on the reception side and the side that leads up from the end of the tour, so you do get people watching you. There’s a place to hang up coats and store bags, you get given an apron and you wash your hands and then you take your station.

I was doing Chocolate Champions, partly because it fitted in best with my schedule and partly because it promised to cover the tempering process, which is one of those things that’s probably better taught than just read about. We were going to make our own customised bar.

Our master chocolatiere was called Geraldine, she wore a head mic (which really didn’t seem to do the job) and she ran it in both French and English. The only bit you really needed translated was the contents of the ingredients jars, which I almost immediately forgot anyway. Everything else you could understand from just watching her, because it was really simple. I’ve done more complex chocolate work with my Rangers, but then I’ve never done it in the kitchen of a proper Swiss chocolate factory, with proper tempered Swiss chocolate fresh from a tap in the kitchen for the very purpose of each of workshops.

First, we took a medium steel bowl for our ingredients – that is, our choice of the spices from the small jars (sea salt, cinnamon, gingerbread, ginger and a couple of others), our choice of textured ingredients (dried cranberries, biscuits, something caramelised and a few more things that I immediately forgot). Then you go to assistant chocolatier Jonathan who doles out ready-melted chocolate in the colour of your choice. I requested a mix of dark and milk. Take that back to your workstation and mix it all well together.

Then we all had a round plastic mould with a post-it note attached so we could write our names. Pour your chocolate mix into the mould. While it’s still solid, go back with your small steel bowl for anything you like to decorate it, which can also include hundreds-and-thousands, smarties and little pink pearls.

Jonathan being a bit over-generous with the chocolate (and especially if you’re having two varieties), Geraldine fetched me a plastic bag to pour the remainder of my chocolate onto – a chocolate dollop, I called it. I decorated my chocolate bar with crushed biscuits and pink pearls and then sprinkled the last of the biscuit on my chocolate dollop. For the record, Geraldine recommended about four spoons of crunchy ingredients but that was nowhere near enough. So far, I’ve eaten the chocolate dollop and I can barely detect anything within the chocolate. There is no crunch. Maybe I just had twice as much chocolate as I should or maybe the ingredients aren’t quite enough to go round a group of 25.

Last step, Jonathan brought round bains marie full of piping bags of chocolate so we could write on our creations. I used dark chocolate to write Cailler, because I’m unimaginative, but the tip of the piping bag was so fine that you can hardly see it.

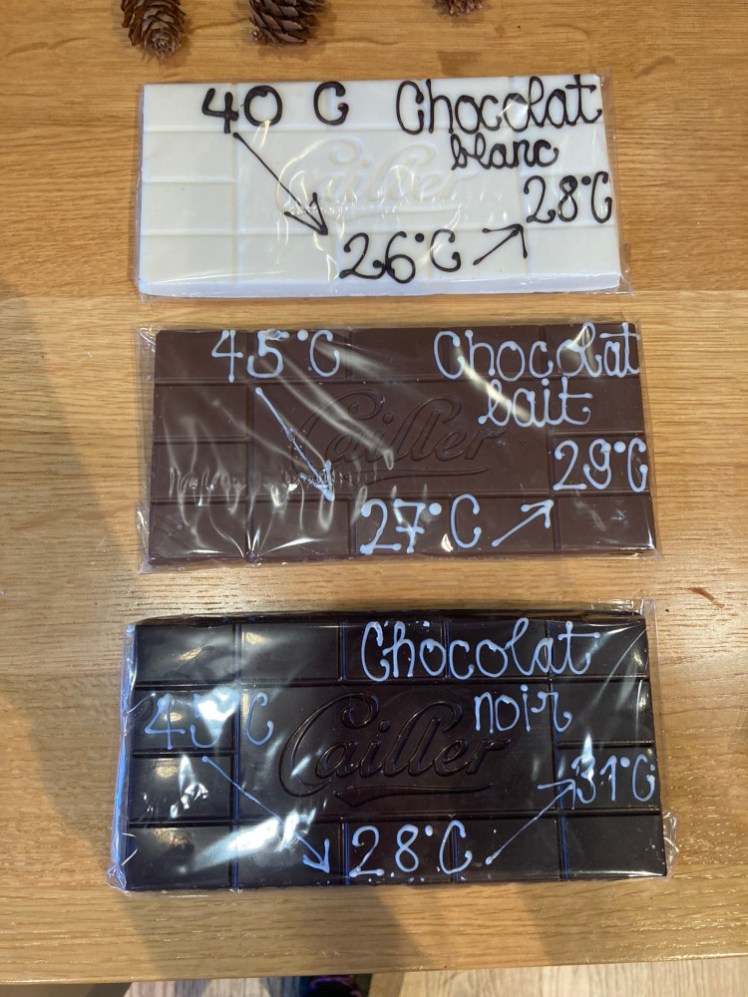

Anyway, when that was all done, we put our creations on cooling racks which were whisked away into the kitchen and then gathered round to learn the mystic art of tempering. Basically, when your chocolate reaches the correct temperature (which varies for milk, white and dark), you pour two-thirds of it onto something cold, like a marble slab, and then manipulate it by spreading it, re-gathering it, re-spreading it and so on until it starts to solidify. Then you return it to the third still in your bowl and the result is a better chocolate. It’s shiny, it makes a nice snap and it doesn’t bloom, which is when the cocoa butter is forced to the surface by water molecules left in the chocolate. It’s perfectly edible but it doesn’t taste as good and it certainly doesn’t look as good. Tempering really means drying the chocolate out and forming crystals.

Geraldine had scooped out a small amount of chocolate as a control before she started this process. By the end, it was still pretty liquid, whereas the tempered chocolate was able to scraped into a little roll, which held its shape. She got out a thermometer gun. The liquid, untempered chocolate, was 21°. “And what about the other chocolate, the solid? Is that going to be warmer or cooler?” Well, I’ve seen QI and that klaxon was going off in my head. I know a trick question when I see one but apparently QI isn’t a thing in Switzerland, because the entire rest of the class said “Cooler!”. And naturally, when tested with the gun, the curled-up tempered chocolate was 22°.

I can follow the tempering process for a batch of chocolate the size I’m likely to handle but I can’t fathom how it created even the three little baths of chocolate we had, let alone doing it on an industrial scale in the factory. Is there a room the size of a ballroom where chocolate-makers armed with broom-sized spatulas squeegee chocolate around from gantries?

But the mystery remains unsolved. We were given gift boxes for our chocolate creations and I slid my chocolate dollop into the plastic bag it had set on. I declined the gift bag – by the end of the day, I’d be on an easyJet plane with nothing but a personal item and that bag was in itself the size of a personal item. No, both the box and the dollop had to be pushed into my bag somehow. Aprons off, thanks for coming, now go and buy some chocolate in the gift store.

Of the two experiences, I’d absolutely recommend the workshop over the visit. I know it’s very simple chocolate-making, of the kind a five-year-old can handle (word of advice; children enjoy the workshop but find the tempering lecture very boring; they have no capacity to appreciate what they’re being taught) but it’s done with good quality chocolate under the supervision of expert chocolate makers, in a Swiss chocolate factory over 120 years old. Honestly, it’s a cultural experience just buying a bar of chocolate here. The Chocolate Champions workshop was 30 CHF (~£28) and they give you a discount on the visit, so I paid 8.50 CHF (~£8) instead of 15. If you’re just interested in the free chocolate, it’s more efficient to just buy a bar of chocolate but if you’re interested in the history of chocolate and the process of making it (maybe the industrial tempering was covered by one of the talking heads I didn’t listen to?), then it’s absolutely worth £8 on top of the workshop to go through. And as I said, the train ride out in itself was pretty much worth it.

If you’re in Switzerland over the summer, there’s a day trip from Montreux which includes a special chocolate train, a visit to the cheese factory at Gruyères and Maison Cailler. I think it’s quite expensive and pretty easy to DIY – you can book the cheese and chocolate factory tours yourself and you can buy a hot chocolate and a chocolate pastry at the station before you set off. The only benefit is that you don’t have to change trains, but you’re not necessarily starting from Montreux, so you might actually find DIYing it means fewer changes.

Anyway, that’s the cheese covered, the chocolate covered, skiing will not be covered but I do have a few more blogs from Switzerland to come, so be back here at 4pm on Monday for the next part.