In my last post, in which I visited Bath Thermae Spa, I called it “bathing like a Roman”, on the grounds that the modern spa uses the same source as the 2000-year-old Roman bathhouse but other than that, there’s no similarity at all between my spa trip and Julia Ennia Caesianus’s visit to the baths. So, what would her visit have been like?

Bath probably started out as a pre-Roman settlement discovered and built up by the Romans. It wasn’t a fortress or a town with any military purpose; it was a resort. The Roman Baths were more extensive than they are today and featured a temple to local goddess Sulis Minerva, an amalgamation of a relatively unknown Celtic goddess Sul, thought to be a water goddess and whose name appears virtually nowhere except Bath, and the Roman goddess Minerva, equivalent of Athena, goddess of wisdom, victory and justice. Why was Minerva chosen as the patron goddess of this place? No idea. Someone like Bacchus, a god of wine, festivity and theatre might have been a good option, or the more obscure Vacuna, goddess of leisure and repose, or even Tranquillitas, the personification of tranquility. But I guess Minerva is a top tier goddess and if you’re going to have one for your patron, might as well go right to the top.

What survives to this day is the main bathing pool and the Sacred Spring. They’re both teeming with parasites and bacteria so you can neither bathe in them nor even touch them. Algae gives them their bright green colour. The main bathing pool is the first big thing you see when you go into the modern museum. I say “modern”. A lot of this is Georgian and Victorian and after many hundreds of years of neglect, even the pools are really archaeological digs. The original Roman bath would have had a huge barrel-vaulted roof, making it one of the biggest buildings in the country. These days, the wooden roof is long gone and most of the building around the pool is Victorian, although there are bits of Roman masonry on display. The main bath is 1.6m deep which is about my height, so definitely more for swimming than bobbing although you could sit on the steps on all sides and there are niches in the stone where there would have been benches and possibly tables. The audioguide paints a very appealing picture of relaxing with a cup of wine after spending time in the more taxing part of the complex.

Those parts are at each end of the pool and are definitely more in the way of an archaeological dig-in-progress. As always, there’s an issue of funding but there’s also an issue that this is in the heart of a working (and touristy) city. The theory is, though, that at the east end is the women’s area and at the west end, the men’s. Both work on the same theory – hot rooms for relaxing in, probably covered in oil, and cold pools in between. In the women’s end, projections on the wall and somehow in the middle of the room show the sort of things going on here – women groaning over massages and panting in the heat and shrieking at the cold water, although most of the noise actually happens over the free audioguide. At the men’s end, you’ve got the noises in the audioguide but the images are left to your imagination.

In both cases, there’s at least one hot room heated by a furnace blowing cold air into a hollow space under the floor, which is held up by hundreds of little heaps of tiles, called a hypocaust. At the men’s end, you can see a hypocaust system in pretty good nick; at the women’s end, it’s a bit more battered, but it’s been out of use for some 1600 years. Up in the hot room, it would have been hot enough that you need sandals to walk around on it; you’d probably have been oiled and then sweated the oil and toxins off, plus a ton of water and electrolytes. Servants – or, let’s be real, slaves – would have then scraped the mixture of oil, sweat and filth off before you move to the next pool.

Essentially, this is a sauna. We have the same sweat-cold-bathe rituals all over the world today. That said, I’d love to open a modern Roman bathhouse, complete with hypocaust rather than modern electric heating system, albeit one that doesn’t require slaves to crawl into the tiny superheated space to clean out the soot. I suppose you can do the sauna-ice-steam room-shower combination before heading to one of the bathing pools right around the corner at the Thermae Spa but I’d like it to be in proper brick and stone, lit by torches and lanterns, rather than the almost clinical white-glass-LEDs that most spas favour today.

There’s also a gym in the men’s area. I daresay they wouldn’t have had the Roman equivalent of gym machines back then but they’d have done exercises and worked up a sweat, just like you might go and do a yoga or spin class at the spa now, if you’re using it as more of a health thing than just a “flopping into the hot water thing” like I do. The women seemed to have a decent-sized swimming pool as well as their hot rooms and cold pools, so maybe that was the kind of ladylike exercise one did back then.

But what you probably won’t find in a modern spa is the religious element, the temple. There’s nothing left of the temple today – or if it is, it’s under the streets of Bath where no one’s going to dig it up for the foreseeable. The triangular temple pediment more or less survives and is displayed in the museum with a projection filling in the gaps where slabs of carved stone are missing. It features a huge carved head thought to be a Gorgon, other than the fact that the face in the middle is definitely male. This is in the middle of a big wreath, presumably laurel, and the whole huge circular device is supported by two female figures standing on globes, with more creatures underneath looking up. No one knows what it all really means. Is this the triumph of the Romans over the Celtic religion? Is it the fusion of the two, as in the double goddess Sulis Minerva? Among the many bits and pieces excavated from the area is a hollow gilt bronze head, probably once part of the statue of Sulis Minerva that stood within the temple.

I haven’t talked about the Sacred Spring yet! It bubbles up right here in the bath complex and is contained within a reservoir and then runs across to the main bathing pool, which doesn’t look like it’s steaming hot, unlike the Sacred Spring. The Spring is about 46°C and 1.17 million litres of water rises here every day. The bubbles constantly coming up aren’t the water boiling but pockets of gas coming up to the surface. I think I saw something in the entrance that said it could fill your bath in eleven seconds but don’t quote me on that.

There’s so much water that the Romans built an overflow drain which carries excess water away under the complex and into the nearby river and it was so well engineered that it’s still the system in use today. Interestingly, the drain is visibly steaming, far more than the Spring’s own pool and it feels hot when you lean towards it, as if it’s boiling, like geyser water in Iceland, despite the Spring only being 46°. The minerals in it have created a kind of yellow-orange layer of thick bubbly stuff all around the drain, probably mostly calcium.

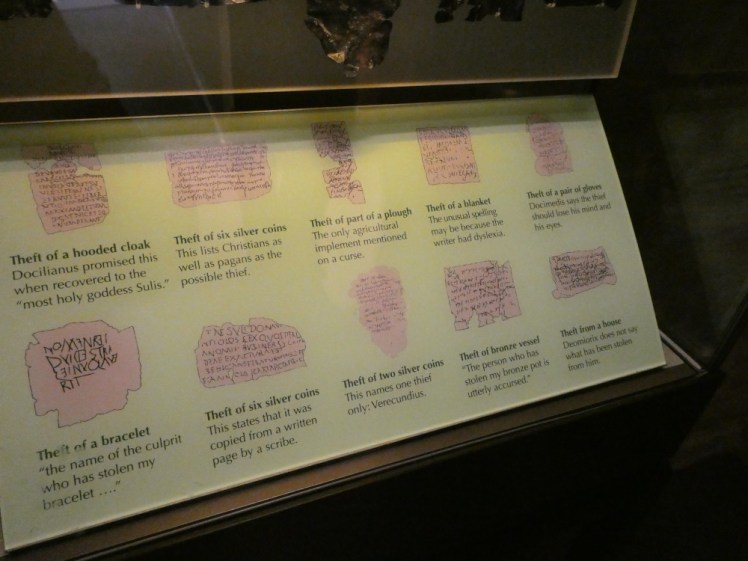

The museum around the bath complex shows the history of the baths, of Bath and what life was like for people in the area. I’m not terribly interested in the Romans as a period of history and very much more interested in hot baths, so I skimmed a lot of it but even I couldn’t miss the amount of stuff found in the Sacred Spring over the centuries. Lots of offerings, lots of (probably deliberately) broken metal plates and jugs and pans, a tin mask, a good couple of handfuls of gemstones and the curse tablets.

Curse tablets, to the best of my understanding, are kind of like the prayer cards you pin up in churches but instead of asking God for blessings and help, these are asking Sulis Minerva to curse those who’ve wronged the writer. It’s mostly things like “my towel got stolen, please curse whoever stole it until he returns it”, mostly personal possessions stolen around the baths but occasionally it sounds like a husband or wife went off with someone else, and that someone else is the subject of the requested curse. Apart from the fact that these are just generally fun to read from the perspective of two thousand years away, they’re significant in that they’re mostly written in British Latin, which is a “vulgar” or popular/colloquial form of Latin so distinct from “higher” or more formal or more Rome-based Latin as to question whether it’s a distinctive language in its own right. It never quite caught on – the Anglo-Saxons brought the language that eventually became English and although we have plenty of Latin influence in the modern English language, most of it has come from from France or Italy relatively recently – probably from the Norman invasion onwards. Two of the curse tablets, however, are in a language otherwise unknown which is speculated to be a lost British Celtic language, of which these two tablets would be the only written example.

I think the Roman Bath complex is very interesting but also very expensive. Standard admission for one adult is £22.50 on a weekday, rising to £25.50 on weekends and bank holidays. You get a free audioguide which you can listen to as and when you want – there are numbers on all the displays (in apparently completely random order) so you can pick and choose what you’re interested in, or you can listen to absolutely everything. It’s entirely self-guided but you can add an hour-long guided tour for an extra £6. For me, I’m quite happy to wander all the wet bits and listen to whatever takes my fancy. It holds various events – I see that there’s T’ai Chi on the Terrace on Tuesday mornings, which might be quite fun and there are apparently silent discos here. Of course, yes, I’d love to see it restored to the point that I could come and bathe here but I think I’m going to have to accept that to do that, you’d lose most of the archaeological details – “here was an authentic Roman brick hypocaust but we’ve covered it all up and put in a shiny tiled floor so you can all lie here and pant just like the Roman ladies used to”, that sort of thing. “We’ve added a ton of chemicals to the spring water so you don’t all die and we’ve also evened up the steps into the bath and added handrails etc”. No, I think a modern Roman bathhouse is going to have to be built from scratch. If anyone builds one, let me know and I’ll come and sample it.

Maybe do Bath the opposite way from the way I did it – come to the Roman Baths first to see how it was all originally done and then go to Thermae to experience it modern-style for yourself. And don’t forget the Abbey before you go home.

One thought on “Bath Roman Baths: how to actually bathe like a Roman”