I was very excited about my tour of the RNLI College but three days later I went back for the boatbuilding tour of the All-weather Lifeboat Centre and that was even more exciting. The College is also home to the factory where the RNLI builds its new fleet of Shannon-class all-weather lifeboats and services, repairs and refits the older lifeboats.

About the Shannon

The Shannon-class is the smallest and fastest all-weather lifeboat. The RNLI has two types of boat – the inshores are the inflatable ones that can get in close to cliffs, caves and shores, and the all-weathers are the big ones with an enclosed wheelhouse. Fifteen or twenty years ago, the RNLI declared that it wanted all its all-weather lifeboats to be able to get to 25 knots in order to be at any incident up to fifty miles out to sea within 30 minutes. That meant replacing some of the slower ones and the solution was the Shannon, the first boat designed from the ground up by the RNLI’s very own naval engineers in Poole, in the glass Support building opposite the college. A note on this building: in any other organisation, this would be called Headquarters or Head Office or something similar but in the RNLI, it’s the Support Centre. The current Chief Executive, due to stand down this month, declared to the staff there “You don’t run the RNLI, it’s run by the volunteers on the coast and you support them” and apparently the entire RNLI danced up and down and went “Yay, someone who actually gets it!”.

The All-weather Lifeboat Centre, the ALC, was built in 2013 at a cost of £24m. Sunseeker, the other big maritime industry in Poole, constructors of luxury yachts, wanted the site but when it became clear they weren’t going to get it, they clubbed together and gave the RNLI a chunk of money, recognising that it would be mutually beneficial to have them right next door. Previously, the building of new lifeboats went out to tender by commercial boatbuilders but the RNLI calculated that by having their own factory and their own boatbuilders, they could save £3m a year while also getting exactly the boats they want. It took until 2018 for them to finally make that saving in a single year but now, May 2024, the building is just about at the point where it’s paying for itself and the lifeboats it makes are “free”. Obviously, they’re not actually free. A Shannon-class lifeboat costs £2.45m according to the RNLI website today and takes around eighteen months to build. I managed to misunderstand something fundamental here – they make four to six a year and generally a new one is launched every twelve weeks. Ergo, I understood that it takes twelve weeks to make a lifeboat from start to finish. I still can’t quite fathom how they’re doing it – there are five stages to the job and it must mean they’re sitting at some of those stages for months.

Let’s go from the beginning. The Shannon-class is the smallest of the all-weather lifeboats at a little over thirteen and a half metres. All its registration numbers start with 13 because that’s how the RNLI numbers its boats. Technically, due to rounding, they should all be 14s but the Trent-class got there first and got the 14 registration. The Shannon is unique in that instead of propellors, it’s powered by waterjets, effectively an oversized jetski, and steered by joystick and the computerised SIMS system instead of the old-fashioned wheel. It has a second helm on the roof and that one does have a wheel but when they’re whizzing out to an emergency, they’ll be inside. The entire boat is watertight and self-righting so if it does capsize in rough seas, it can flip itself up the right way. For this reason, it has shock-absorbing seats and six-point harnesses. It has six seats upstairs for five crew and a doctor and a casualty space downstairs with six more seats, plus space upstairs to tie down a stretcher. However, if it needs to, it can pack around 70 people on board. It has a nominal top speed of 25 knots, just under 29mph, but “you’d be pretty disappointed if it couldn’t hit 32 knots”. Those waterjets mean it can go from 28 knots to a dead stop in three seconds and in two boat lengths – again, see those harnesses – and it can move sideways to come alongside easily. It’s a pretty amazing boat just as a boat.

And no, they won’t build one for you – they’re not commercial boatbuilders, they have a production schedule and they don’t have the spare space in the ALC. Maybe you can buy a used one but the Shannons are intended to have an operational life of 50 years and when the RNLI gets rid of boats, it sells them – in order of preference – to other lifeboat organisations overseas (what’s old and obsolete to the RNLI is often cutting edge to other organisations), to harbour masters as pilot boats and then to members of the public, subject to vetting – the RNLI is not keen on selling, for example, to drug runners. The first Shannons are about eleven years old by now so in just under 40 years, you might be in with a chance.

The engines are modified Scania truck engines, limited to 650hp although in the trucks, they can go much higher than that. They burn through 20l of fuel per nautical mile, have two fuel tanks each of around 1300l, one for each engine and the said “tanks” are actually polythene bags so that they don’t leak if the hull is punctured. Interesting fact: the RNLI pays VAT on fuel they use during shouts but not during training. Apart from the issue that if the RNLI don’t train, they can’t rescue, what do you say when you present the receipt? “We anticipate this many rescues, lasting this long, travelling this far, so this is how much fuel we’ll use on emergencies and we’ll use this much on training, so this is how much VAT we should be paying on it”. I daresay the accountant at my previous company could manage that just fine but it’s entirely a matter of predicting an unpredictable future.

Anyway, on to the building!

Building A

We start in Building A, the “sticky building”. This is where they make the frame of the boats. They have a mould for the hull and a mould (which they use upside down) for the wheelhouse and they line in with a special composite material, high density fibreglass backed with a sort of resin that comes on rolls and pretty much looks like patterned sticky-back plastic. This stuff has to be kept in a freezer when it’s not in use, otherwise it goes off in just two weeks. Once it’s out, it can only be used at 17°, so on chilly Monday mornings in January when the heating hasn’t quite kicked in yet, the boatbuilders have to just sit and wait for it to warm up.

They sandwich the composite material with a layer of high-density foam, about 1cm thick, which comes pre-cut and pre-drilled from the manufacturer, then the mould is sealed up in a cover that looks like it’s been wrapped in plastic bags, a vacuum hose is attached, the lid is pulled over the mould and the whole thing is heated, with the mould under vacuum, to 85°C for 16 hours. Actually, it only stays at its top temperature for half an hour or so, the other fifteen and a half hours are bringing it up to temperature and bringing it back down. The heat melts the resin and the vacuum sucks it into the foam via the pre-drilled holes, fusing the two layers together. That process is repeated three times and then you have a lifeboat!

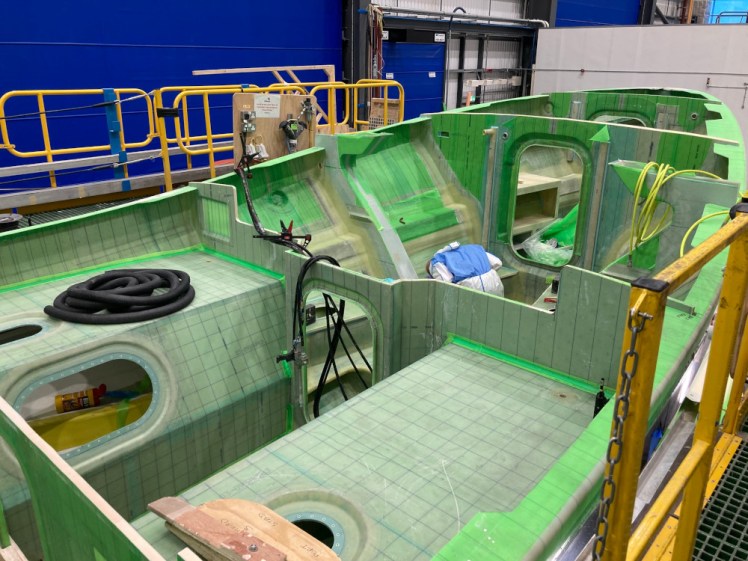

Stage 2 is to put in all the other bits. You might have the frame of a lifeboat but there are still 130 other pieces that need to be moulded and fitted – all the bulkheads and bays and supports and other bits that I can’t even fathom.

The two buildings are really interesting. For a start, they have huge blue roller doors to allow the boats to be taken outside but the effect is kind of like you’re on a film set and someone’s going to paint out the background and put something else in. There’s a lot of lime green fabric and tape used – no idea what for; we watched someone line all the corners and edges in the stage 2 hull with it, and that adds to the effect that something’s going to be CGI’d in later on. Second, they’re really tidy and organised in here. There are shelves and boxes and labels and the tools have a place and there’s no dust or dirt or flakes or anything on either floors or surfaces. We were asked to not touch anything because it’s sticky but honestly, other than the roll of composite materials rolled out onto the table, I didn’t see anything that looked at all sticky.

Stage 3 is painting. Painting is in Building A but it’s accessed only by doors outside because they don’t want any sticky or any dust to get into the paint. This bit isn’t open to the public but it’s where they paint the hull navy blue with the red and yellow stripes and paint the wheelhouse orange.

Building B

Next is into Building B, where they actually do the building. There are eight bays and at the moment, the first two are used for building new Shannons. The other six are for refits, repairs and anything else that the existing fleet requires. When I was there, the first one was for a boat in Stage 4 and the second for Stage 5 but they alternate, they don’t move a boat over into the next bay just because it’s reached the next stage. The stage 4 wheelhouse sits in the middle and is either popped onto the boat on the right or the left, depending on which side its partner is on this time. From my point of view, to watch the process happen from left to right like I’m reading a book makes more sense than seeing it from right to left but if you come back in the summer or autumn, you’ll probably find the boat in two halves will now be the one on the right and the one on the left, the one in two parts today, will be the nearly-completed one in stage 5. The stage 4 boat at the moment is bound for Hartlepool and Wikipedia says it’s going to be called John Sharp.

Stage 4 is fitting out the boat, putting in all the electronics and the engine and putting everything together and basically making a working lifeboat. Stage 5 is putting the two halves together and finishing it off. Up until this point, the hull and the wheelhouse have been two separate parts – they’ve sat next to each other all along but this is the first time when they get joined together. They spend some time lining up the two parts perfectly but they don’t actually touch, there’s a gap of about a quarter of an inch between the two and at this point, the sticky people from Building A come over, the only time in the process they come into Building B, and they fill the gap with resin and then bake it. That means there’s not a single nut or bolt used and the boat is absolutely watertight.

This building is the same size as Building A but because it doesn’t have any of it partitioned off for the painting area and it doesn’t have multiple floors, it looks bigger. I mean, it does have multiple floors in that there’s the floor we were walking along, just above the lifeboats and there’s also work going on underneath them but Building A has a load of stuff tucked away underneath, the moulding is done in a raised area at the front while stage 2 is done in the open beyond that and it’s got levels with low walls along the sides where stuff is stored and made and whatnot. Building B has the same blue doors but now they’re along the entire side of the building instead of merely most of it and you’re facing them. It’s surprisingly light and airy, actually – it’s only now that it occurs to me to wonder if there are any windows because I don’t remember seeing any.

The boats come to the builders, they don’t go to the boats. You’re not required to pick up your tools and move from bay 4 down to bay 10. If you’re needed on the boat in bay 10, that boat will come to you. Or rather, it seems like if you’re working on building Shannons, that’s where you’ll stay, and if you’re refitting Severns, that’s where you’ll stay, and if you’re doing random repairs on whatever’s in that day, that’s where you’ll stay. That feels a bit monotonous to me but perhaps it’s better to have everyone specialise when it comes to lifeboats. As I said earlier about everything being tidy and organised, boatbuilders are apparently able to find their tools in the dark because they should always be put in their correct place.

After building

Once a boat is completely finished, it’s taken outside and launched onto Poole Harbour with a little ceremony where they ring eight bells, the traditional signal that a new watch has started. It spends a couple of months in sea trials, where the testers “try to break it” because if there are any defects, it’s better to find them during trials than during an emergency. But that’s not the end of the Shannon’s story. It can’t go operational until 70% of its crew are assessed as competent in its use, and that can take up to six months. So if they’re replacing an older model with a Shannon, the older boat has to stay at the station until the Shannon is operational, and must be used on shouts until that time. That can be inconvenient because most boathouses aren’t designed to house two all-weather boats but it’s better than a crew heading out on a emergency in a boat they have no idea how to drive and remember, the Shannons are quite dramatically different in both operation and mechanics.

If I understood correctly, only one person is trained in use of the Shannon at the College in Poole but I may have misunderstood. Anyway, the Shannon is transported to its new station by its future crew so they can get used to it in non-emergency conditions along the way. If they’re going a long way, they might make a crew swap partway, which means everyone gets a go on it and also means the station is never left unmanned. Then the rest of the crew is trained over the following six months or so and assessed by regional assessors – not by their own station trainers – and only then can it go operational.

Other services

So that’s the Shannon side of the story. But the ALC also repairs and refits their existing boats. Every class of lifeboat has a certain refit cycle – the Severns, conveniently, are every seven years but the Shannons are twelve. They’ll come in for 13-20 weeks, depending on the class, and anything that can be removed will be removed. It’ll all be checked, repaired or replaced if necessary, put tidily behind or underneath the empty lifeboat, the whole thing overhauled, everything put back in, and when the boat is ready, it’ll be sent back. The Severns have a lifespan of 25 years but they’re good boats, powerful, big, and the RNLI isn’t ready to let go of them yet so in their life expansion programme, the oldest ones are being gutted, completely refitted with new kit, new engines and effectively have become a brand new boat in an old shell. A new one would apparently cost £26m – bit of a jump from £2.5m for a Shannon! – but it’s only £3m to completely refit a Severn, so that seems a better option at the moment.

They also get serviced and repaired. There’s currently a very early Shannon in there which isn’t hitting the speeds it should be and they can’t figure out why. It works out of Dungeness, so it does a lot more rescuing of small immigrant boats than other Shannons, so it contains more kit than the average Shannon but it shouldn’t be enough to slow it down. So at the moment, the engine manufacturers are talking to the waterjet manufacturers and trying to figure out where the problem might be, and the RNLI are going to weigh it and see if it’s put on any weight. They can’t think why it would but they want to be thorough. Can’t even be a lifeboat without being accused of putting on too much weight!

And I think that’s it. I think that’s a pretty comprehensive write-up of the boatbuilding tour. I really enjoyed it and if you’re ever in Poole on a Monday morning or Wednesday afternoon, do give the RNLI College a ring and book yourself onto the tour.