In November 2021, a man was severely injured in an accident in a cave in south Wales. The subsequent rescue involved around 300 people and took 54 hours. It made national news. It made international news. I wrote a blog post about the complexity of the cave and why it took so long. And now BBC Wales have made a docu-drama about it., called The Rescue: 54 Hours Under the Ground. Well, they did it a while back but it’s taken me some time to watch it.

The background: the cave in question is called Ogof Ffynnon Ddu, the Cave of the Black Spring, and known almost universally as OFD – it was odd how many times it was referred to by its full name in this film because the only time you use that is when you’re telling someone new what OFD stands for. It has three entrances and stretches pretty much from the top of Carreg Cadno down into the valley a couple of hundred vertical metres down. The casualty, George Linnane, went in the middle entrance at Cwm Dwr, which is a particularly tight, crawly space and was caught in a minor boulder collapsed which resulted in him falling eight metres through the rocks, breaking his jaw, leg and something in his chest. You can’t take a stretcher out through the Cwm Dwr entrance, so he had to be taken out the top entrance, which is a good day’s caving when everyone has full use of their limbs. A rough rule of thumb, according to George, is that an hour’s caving takes ten hours with a stretcher, so they were actually pretty quick – it was about three hours before the stretcher got to him, so the actual carry was around 51 hours and I’d say five hours from Cwm Dwr to top is good going.

This isn’t about the cave or the rescue, per se. I’ve already talked about what little I know of that and I don’t have enough days in my life to say all the good things I want to about cavers and cave rescue. They all did a magnficent job. It’s about the BBC Wales docu-drama.

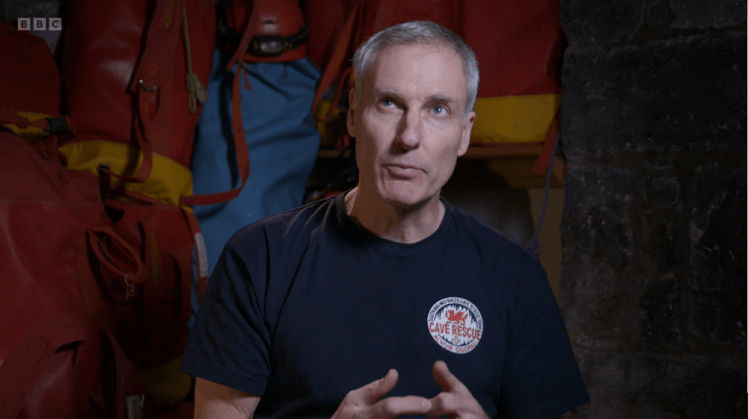

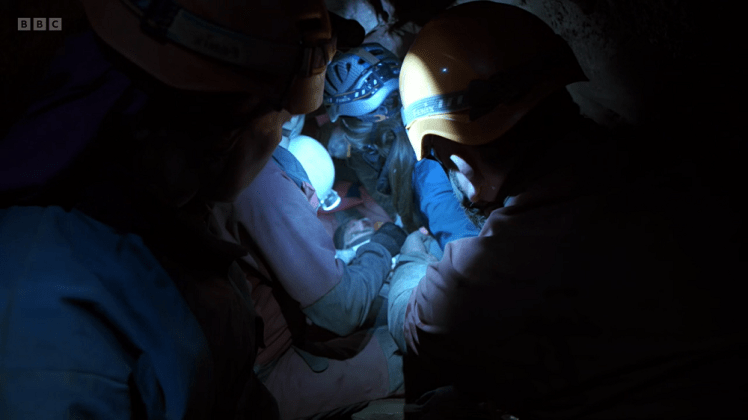

It features talking heads interspersed with recreations of the event – George’s caving companions talking about the accident, George talking about his experience, controllers talking about how it all worked, and so on, plus some rather beautifully-shot scenes inside the cave. I don’t think anyone was doing much filming or photographing live. Everyone had their hands a bit full. But speaking of photos: the media got hold of this – BBC Wales turned up at the South Wales Caving Club in the thick of it all, and the media in general, of course, wanted photos. They catch people’s attention. They can’t take their own this time, since it’s happening in a specialised environment literally inside the mountain so they asked one of George’s mates, Mark Burkey, the man who raised the alarm in the first place and who is a cave photographer, for pictures. Caving is a niche sport, to quote someone in the film. Surface-dwellers find the whole idea horrifying – it’s dark and enclosed! – and of course, they want to push the horror of this incident, at least in the early days because horror sells newspapers. So they were asking Mark for photos showing that narrative, that caves are terrifying and caving is extremely dangerous.

There was no need for the ominous music and lime-green graphics. I know you need to re-build tension after destroying it in the first few seconds by showing George alive and well and talking about the ordeal, but lime-green digital clocks ticking the hours away and lime-green cave surveys are just too much – this isn’t a cheap thriller where you have to shove everything right into the frontal lobes of popcorn-munching idiots. This is a BBC documentary. And the horror and tension shouldn’t be front and centre.

What should be front and centre is the caving community, and when they turned down the graphics and music, that came across very well. Cavers are a bit of a unique species and I liked all the talk about comrades and friends. “Cavers are the only people who can rescue cavers,” says George. Again and again it was pointed out that these are volunteers and that they’re coming from all over the country and that you keep running into faces you recognise from other regions. I haven’t been caving properly for fifteen years and when they listed everyone involved in the rescue over the closing shot, even I recognised four names. If you take nothing else from this film, take that the caving community is close-knit and they look out for their own.

It’s well done. It’s really good cave filming and under other circumstances, I’d be raving about how beautiful it all looks. It’s very easy to forget that the BBC must have sent a film crew up one weekend, gathered together any cavers that would come, and basically staged the entire rescue, which includes carrying a lot of gear up to OFD Top and dragging it at least into the streamway. Incidentally, of course that canyon, the 60ft pitch, needs rigging for hauling a stretcher up but it did make my blood run a little bit cold to think that fifteen years ago, I’d slide down that thing with no ropes, no safety gear, no protection. Cavers are mad. You wouldn’t take ropes and hardware into OFD, you just don’t need it. A 60ft pitch, a canyon, with no protection! I don’t even remember it being particularly scary. It’s smooth wavy walls and you just wedge yourself in however’s appropriate and kind of Spiderman your way down. Maybe I’m misremembering. Tell me I’m misremembering!

It’s very petty to complain that the further the film went, the higher towards Top entrance George was taken, the more often you saw crews of replacement rescuers striding across Cwm Dwr. It’s a bit of a hike up to Top entrance but it’s an hour or so down to George once you get underground rather than four hours up. There’s definitely a point when it’s just inefficient and pointless to go in the Cwm Dwr entrance and the cavers absolutely wouldn’t have done that. Maybe the camera folk didn’t want to hike up the mountain to film multiple teams going in the real entrance. But hey, it does all look very good. Helpfully, they filmed it on a sunny day, whereas it was rainy and foggy and horrible at the time – I’ve seen videos from outside the SWCC and it’s also the reason they couldn’t send an air ambulance to pick George up at the end of it all. Yeah, even underground, the weather plays a role.

Well done for including all the folk on the surface, by the way. The people under the ground and the SMWCRT controllers get a lot of the glory – and fair enough, really – but you can’t underestimate the people back at the hut who are feeding the rescue effort, running down to Ystradgynlais or Pontardawe for food supplies, charging lamps, finding, cleaning and organising kit, photocopying sections of the survey to guide people around the cave, keeping the fires going, keeping the press out from under everyone’s feet and doing everything that’s needed to support the expedition. That would be me. Tesco runs, fetching and carrying, directing car parking maybe. I’d be a liability underground, even in my heyday, but oh, how I can organise an event!

No mention of the aftermath. There’s just “everyone clapped” when George popped out into the fresh air, taken off in an ambulance and that’s it, show’s over. In actual fact, there would have been a lot of stuff just dumped underground because no one’s got the spare hands to carry anything that’s not absolutely essential. Someone’s got to go and derig and someone’s got to collect up the stuff. I 1000% would not expect that to be done immediately but over the next weekend, it has to be derigged before anyone uses the ropes unwisely or the hardware goes rusty, and probably anyone who went down there for the next couple of weeks must have been asked to bring out anything they find abandoned. There’s a lot of people who’ve got to walk back down the hill, be fed and find a bed – they would have been popping out around early evening on Monday, I think, and most people will have come a considerable distance. Not the kind of distance you’re going to want to drive in the evening after a long rescue shift. The hut has to be tidied and cleaned – you can’t just run off home and leave wet muddy kit dropped wherever you left it and catering for 300 unwashed for the warden to deal with. No, the rescue may have been over by Monday evening but that hut wouldn’t be quiet and empty again until at least Tuesday evening. And if I know cavers, Monday night involved a lot of beer and vodka. I know the film wants to show George’s story but I’d have liked to see just a little of the few hours immediately afterwards.

Yeah. If you’re at all claustrophobic, you’re going to find this a bit of a horror show. This is the worst case scenario of something you’re already seeing as absolutely hellish. This is a nightmare. Multiple serious injuries, in the dark, in the wet, under a mountain. But if you’re a caver – or maybe mountain type or a climber or you do some activity that also has a sense of community – this is actually quite a heartwarming film. I wasn’t particularly distressed about George – I know those 54 hours would have been the worst of most people’s lives – but we knew he would be ok. No, it was the cave rescuers all coming together, talking about rescuing your friends and calling on your comrades, that made my eyes prickle. I’m not one of them anymore but these were my tribe. George is right, cavers are “bloody-minded” and they’re often weird and nerds but they’re also extremely practical people. People who do things and people who will find a way around any obstacle, whether it’s physical or metaphorical. Cavers don’t daydream or antagonise or meditate: cavers fix things and solve problems and this time the problem was “how do we get an immobile man out of a big cave?”.

One last thing: for all the times they said in the film that this was unprecedented, it wasn’t. I’ve said it before. A member of my club was at the centre of a similar rescue in 2005. In her case, she fell in much the same area and broke her spine. Her rescue, which took the same route, only required about 150 people and only took about 28 hours and because it was 2005, it didn’t make social media or attract the media’s attention. I know it’s been dwarfed by George’s rescue but I’d have liked someone to acknowledge that SMWCRT isn’t entirely inexperienced in rescues of this kind. You can read the report here, incident number 13. You can read George’s report here], incident number 23 – whoever writes this had become much more succinct over the years because it’s just one paragraph. Actually, the cave rescue reports are quite interesting. I particularly enjoy incident 16 in 2007, when a caver got his knee trapped in a fissure. I quote: “Although drills, plugs and feathers, hammer, chisels and washing up liquid were available none were needed or used”. I just love the idea that washing-up liquid is an important tool in cave rescue’s first aid kit.

But that’s all by the by. On the whole, The Rescue: 54 Hours Under the Ground is quite a hard watch and your attitude to caves is going to massively colour your feelings and reaction to it but I think one thing we can all agree on is that cave rescue is amazing and if you’d like to donate to SMWCRT, their donation page is here. Yes, they’re all volunteers but that doesn’t mean they don’t need to fund equipment and training.