While I was at my cottage last week, in a rural bit of Somerset, I wanted to go for a walk. I had my daily 2km to walk – yes, even when I’m on holiday – and I’d invested in the cutest map.

I knew Ordnance Survey offer custom maps (see my Single Map series for my use of my own, the big one I’m holding in the picture above) but I didn’t know about their mini custom maps. They’re teeny little A3 things in a slightly thicker, shinier leaflet-like paper rather than the papery paper the bigger maps use, much easier to handle than a full-size OS map and definitely suited to things like a short holiday where you just want to do a couple of interesting pleasant strolls. They extend about 10km across and about 6km up, which was plenty of scope for this mini break. At £6.99, they’re not such a bad price, especially if you’re ordering it for a special reason – “here’s the map centred on our first home together” etc – and it’s certainly a lot cheaper than the full-sized custom map which is £16.99 at the moment. On the other hand, I could buy the standard OS155 map which covers Bristol, Bath, a chunk of the Forest of Avon, quite a bit of the Cotswolds and even a hint of the Mendips and the entire area around Marksbury for £8.99.

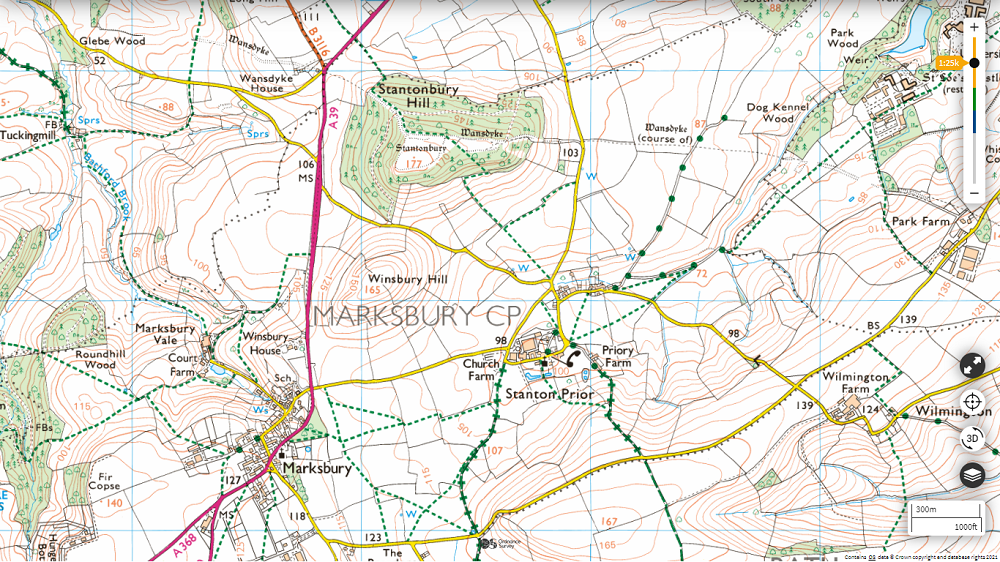

I’d put Marksbury, my village, in the middle of my custom map and on Monday, I unfolded it and had a quick look for a nice obvious walk that would occupy me for an hour or two. Yes, there it was. A footpath which started next to the church across the road, went east to the village of Stanton Priory and then, up a yellow minor road, was another footpath that went up Stantonbury Hill. I’d go up and then follow the main road straight home again. I didn’t measure it but a rough guess via how many grid squares it crossed said not more than about two and a half kilometres to the hill and less back.

I hadn’t packed much. I hadn’t exactly had lunch before setting out but I’d eaten after a fashion, and after a late breakfast, so I filled my bottle, dropped my first aid kit and compass in my bag with my hat, put on my boots and my waterproof jacket, decided not to bother with the waterproof trousers and set out with my phone, two cameras and my mini map in assorted pockets.

Finding the start of the walk is always the hardest but. I crossed the road, realised there was no pavement beyond the graveyard and had to cross back, at which point I noticed the footpath sign less than ten metres from where I’d just been standing.

The footpath goes through a bit of private woodland, where corrugated iron shelters and wire fencing suggests animals – a handful of pigs, for my money, although no sign of life today. At the end was a gate and I emerged into a field. There’s a clear track etched straight across the middle although the crop, which seemed to have been sweetcorn, is utterly flattened at this time of year.

This field is a strong contender for the worst thing I’ve ever walked across. It looks innocent but it’s actually very sticky mud. Maybe even clay. It’s the sort of thing that coats the sole of your boots and sticks out a couple of inches in all directions within four steps. Another four and you realise how much it weighs. No point in wiping it off – there’s nowhere to do it, anyway, and you’ll only pick up a new lot in seconds. But it does ruin your grip and it turns out that matters, because you also have to pick your way across hundreds of rocks.

The second field is more grassy and then in the third, you have to consult the map, having peered long and hard at the path marker and the overgrown and unusable gate, before deciding the path goes down the right-hand side of the hedge. Then you’re in the last field and really only have the thick wet mud to negotiate to reach the gate and step out into the village.

First is the farm. It probably owns the fields I’d just walked through and judging by the bellowing, it also has cows. I followed the country lane away from the farm and towards the hill, listening out for oncoming vehicles. On a single-track lane like this, all you can do is stop and press yourself against the hedge but on a Monday afternoon in December, I only saw one vehicle down here.

Then you come to part of the village. It’s that nice yellow limestone you get all around here and it looks lovely. Not that Marksbury isn’t just as pretty, in quite a similar way, but Stanton Prior doesn’t have a major A-road running right through it. If I wanted another holiday in this neck of the woods, I could do worse than Stanton Prior.

Now I just had the hill to climb. Another clear track up the middle of an empty winter field, followed by a climb up the side of a field that seemed mostly bracken. Above this was woodland encircling the hilltop like a monk’s tonsure, and then above that, some unwell-looking crop I can’t identify and something that looks like bamboo. Because of the woods, you can’t actually see anything from the top and because of the crop, you can’t see that this is anything other than an ordinary hill looking a bit scrubby in winter.

In fact, this is Stantonbury Camp, an Iron Age hillfort. Knowing that, you can suddenly see it on the map, that this isn’t an ordinary boring hill like Winsbury Hill immediately to the south. I’m not a great expert on hillforts. To this day, I don’t know how much is the natural hill and how much was built or reshaped or whether it varies depending on raw hill available but I’ve climbed enough of them to know that there’s something about them you can see on a map. I can’t make out much on the ground, although my investigations on the subject lead me to the idea that other people, who do know what to look for, can see bits of the remains.

If you know even less about hillforts than me: they’re Iron Age earthworks. Iron Age sounds hundreds of thousands of years ago but it was the period right before the Romans. In fact, they often overlapped. The existing Iron Age fort-dwellers fought fiercely with the invading Romans in this corner of the country. In other places, they co-existed as peaceful neighbours and many the arrow-straight Roman road you’ll find running directly from one hillfort to another.

They tend, in my limited experience, to be a bit on the oblong side rather than a nice circle. They’re made up of ditches alternated with higher banks – walls, effectively, before people had mastered building solid defensive walls. There was usually a gap at one end or two, often to the east or west and these were something of a maze, so that intruders took so long coming inside that someone spotted them. I think they sometimes had wooden walls or gates but as we’re talking two thousand years ago for the youngest of them, anything wooden is long gone.

Effectively, they’re small cities. They’re defensive structures, meant to keep outsiders out, but entire communities and their livestock would have lived on top. There are often burial sites on various shapes and styles on top and it wasn’t beneath the Romans to add a temple of their own to any that came into their hands.

Small hillforts are marked on maps with earthwork symbols, so they’re easy to spot. The bigger ones, like this one, are rings of concentric contour lines packed closely together. It can be just a hill but they’re also sometimes wooded and a big green circle, like Stantonbury Hill, on a map generally screams hillfort.

One thing I found interesting is that Marksbury used to be called Stantonbury. At least, that’s how I’m reading it because the website really makes it sound like it’s the other way round. But then, maybe the locals do call it Stantonbury. I live near a village that has one name on its road signs and on maps but which is called something altogether different by its residents and even Wikipedia acknowledges its second name in brackets. I’m not local here so I’m taking what little information I have. It’s now Marksbury. Maybe it used to be Stantonbury. Stanton Prior, and its Priory Farm, was clearly a priory, a religious centre a little less in prestige than an abbey or monastery, near Stantonbury village, then. In this case, it seems Stanton Prior belonged to Bath Abbey. No surprises there, now I’ve figured out priories, except that the manor of Marksbury belonged to Glastonbury Abbey. Just as you think you’re untangling things, another huge knot comes along.

But more interestingly, Marksbury probably came from Merces burgh or Maerec’s burh, which means boundary fort and means pretty much the same as Maes Knoll. You can read that here, in almost exactly the same words, except the bits about local vs official names, priories and abbeys, but from someone who knows much more about hillforts and the area than me. The reason that’s interesting is that Stantonbury Camp is on the route of the Wansdyke, Woden’s Dyke, a long early medieval earthwork, which seems to be in two parts, an east and a west. Was it once a single unbroken thing? Probably – I think. A local boundary for a small kingdom (or equivalent) now lost in time?

Stantonbury Camp is along the West Wansdyke and its western end seems to be marked by another hillfort, called Maes Knoll. Yes, two hillforts with basically the same name. One man, Maerec, who gave his name to both forts? Or does it literally mean boundary fort and the builders were just really unimaginative?

I wish I knew enough about earthworks and hillforts to say anything intelligent about either of them, apart from that even a muddy hill on a winter day can have hidden interesting depths. Now I know it’s there, I can see the course of the Wansdyke across my custom map but Maes Knoll is an inch or two off the top corner. If I’d bought that OS155 map, I could have examined that hillfort very happily.

My plan to go back along the A39 was scuppered at this point. I could make out glimpses of it between the trees, not enough to see much detail but enough to realise that although there was pavement through Marksbury, it was likely to not have that outside the village. Later, I’d discover that about half of that stretch of road was a dual carriageway. It turned out it was a pretty good decision to not walk down the north-west side of the hill and follow the A39 back, but instead to retrace my steps. Back through the woods, back down the hill, back through the nice quiet village, back across the clay field and the maybe-pig trees and back into Marksbury.

One last small issue: I had a solid inch of thick clay on the bottom of my boots. I couldn’t walk into the cottage like that, and my attempts to scrape it off on walls, fences and rocks had made very little difference. That mud had also splattered up my trouser legs. I sighed. I unlocked my cottage, took my boots off outside and stepped onto the mat in my wet socks. Peeled them off, and then unzipped the lower part of the trousers and zipped them off altogether above the knees. Socks and trouser-legs straight into the washing machine, then I put on my sandals and took my muddy boots out to the car, where they remain still. The cottage remains clean and because I’m a grown-up, I figured out how to use a strange washing machine to get the mud out of my trousers and socks, simply so they were in a fit state to be shoved into my suitcase when I left on Wednesday.

And that was my walk! (PS, I’m not sponsored by Ordnance Survey but I’d love to be! Get in touch, OS, I have some thoughts on maps I’d love to put into practice on this blog!)