The third post of the Polar Bear Winter Festival is another winter-themed one – well, an ice-and-snow-themed one, anyway. It’s a Travel Library post and it’s all about A Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter, the Austrian wife of a scientist of some kind turned fur trapper who spent a year living with him in a tiny hut on the north coast of Svalbard.

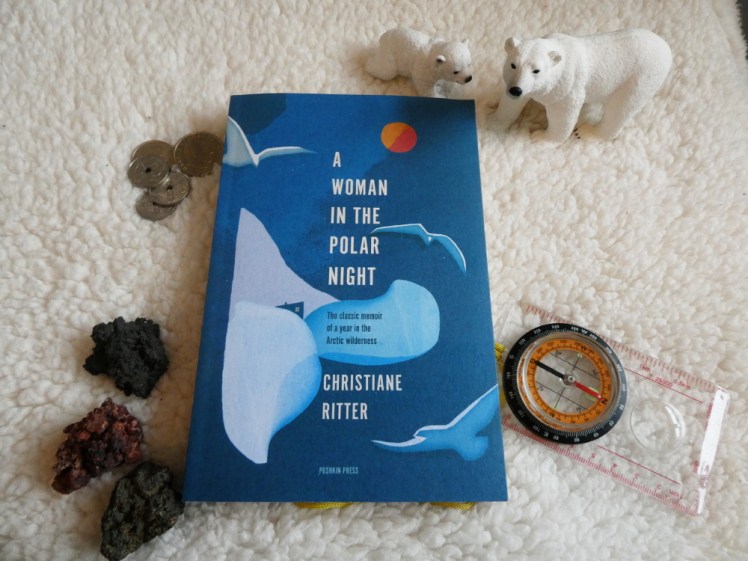

A Woman in the Polar Night was published in 1938 and although it’s never been out of print in Germany, it only reappeared in English for the first time in several decades in 2019 and it happened to be lying on the “why not try these?” table at the bookshop when I went to look at books as a self-reward for having my second vaccine. Obviously it caught my eye – it’s a very pretty book, with an unusually matte cover and a stylised image of the snow and the birds and the sun being somehow dimmer.

The first thing to get past is the twenty-first century instinctive revulsion that this couple were living in the Arctic as hunters – well, Hermann and their friend Karl who lived with them were hunters. Christiane was their housewife, which mostly entailed sitting in the cabin trying to stay alive while the men were out hunting, trying to keep the place clean and be in charge of the food, although they did take turns with the cooking when the men were at home. I understand and sympathise with killing seals and polar bears for food if you live in the Arctic wilderness but I can’t quite square it with the idea that they chose to move up there, especially as they chose to move there to kill.

But we’re going to get right past that and leave it behind because this is quite a lovely tale of solitude and snow and nature and seasons, living an incredibly hard life in an incredibly inhospitable place. Very few of us could live in such a tiny cabin, in absolute darkness for several months, perpetually covered in soot from a malfunctioning stove and depending on driftwood to not freeze to death, to say nothing of surviving on a few tins and such animals as they could shoot and butcher themselves. Forget leaving with the postman, who turns up some nine months into their stay; I’d be waving down passing ships with twenty-four hours. These days Longyearbyen is a fairly substantial little town but it’s still 140 miles from Grey Hook, where the hut was, and in the 1930s it sounds like little more than a couple of mines, and certainly not a thriving local capital.

Christiane not only adapts to her new life, she falls in love with it. Given an opportunity to leave early and return to Austria and civilisation, she declines despite the best efforts of her husband and Karl and stays for the full year. Returning to the steam ship that will sail them home – or sail her home and drop Hermann off at his next job – is a shock to the system. After a year of eating dried seal and polar bear and celebrating New Year with surgical spirit, “real” food tastes weird and they yearn for the chunks of seal another hunter is carving up on a nearby table.

For all the difficulty, though, Christiane spots the beauty in her new world, the colours of the sky and the sea and the snow, the wildlife around the hut that isn’t as scared of the humans yet as they should be, the merits of a life with next to no possessions, a simple life with nothing to do but survive and eat. It’s not quite her fond hopes to “stay by the warm stove in the hut, knit socks, paint from the window, read thick books in the remote quiet and, not least, sleep to my heart’s content” but in its way, it is that quiet simple life.

It’s only really when the post arrives, after nine or so months, the first visitor from outside their little bubble of Christiane, Hermann, Karl and a lot of dead Arctic wildlife, that you really realise how isolated they are – Christiane and Hermann are Austrian and they want to know if war has broken out. Nothing has really changed up in this highest part of the High Arctic in hundreds of years and this book could easily be set much longer ago than ninety years. While these three are finding driftwood and beheading foxes and trying to keep the soot out of the hut, Hitler had already taken over Germany and World War II was already visible on the horizon. It was a bit early for it to have actually started but it could have been raging over Europe and Christiane and co would have been cheerfully oblivious, in their little hut in the snow.

And yet – there was a teenage daughter who gets one mention in the book “But at night I am calm. I think of my child at home and it gives me peace”. That’s the only mention. What happened to her while her parents were off killing foxes in the Arctic? When they were expecting war, did they worry about her? I know, when men write books of their adventures no one even thinks to ask “what about the wife and children?” and I don’t want to do that here. But both her parents are away and they apparently spare their child no thought at all for a year and it just makes me wonder. What was she doing? How did she feel about it? How did living parent-less under Hitler’s rule affect her?

Women doing weird, adventurous stuff is quite accepted these days – well, in general rather than specifically in your office of bored unimaginative housewives who can never resist asking “what, on your own?” – but this is the 1930s. Christiane was the first woman to ever spend winter so far north – or perhaps we should say the first western European woman. She avoided telling anyone on the steam ship over what she was actually doing and the passengers on the return journey are “baffled” by the “ragged passengers with faces burnt dark and clothes bleached white, their boots leached by seawater and stained with the blood of seals”. She was a pioneer, and one who’s largely been forgotten. The book describes her an artist and author, although she never published anything else and I can’t really find anything – at least in English – about her except this book.

I will probably never do it but I’d like to live in Svalbard for a year. I’d live in Longyearbyen, with access to the supermarket and pool and internet, so a very different life to Christiane’s, with my remote job keeping me tied to my laptop for most of the day, and if I did ever do it, I’d write a book. But it would be a clunky thing. A Woman in the Polar Night is a jewel.