Going inside St Basil’s Cathedral is exciting but it’s not exciting like going into the Kremlin. Even though it’s a standard tourist thing to do in Moscow and a lot of it is now a museum complex, it stills feels illicit, transgressive, as if you’re breaking into a high-security spy headquarters where ordinary civilians, let alone urchins, are not allowed to go.

We’ll ignore the indignities of buying a ticket (the queue through Alexander Gardens is for Armoury Chamber tickets; tickets for Cathedral Square/general entrance don’t actually have queues once you get inside) and going through security and removing everything from your bag into the five pockets secreted around your t-shirt because a previously reliable bottle has emptied its contents into said bag. I walked up to the Trinity Gate Tower and strolled through the Kremlin wall and into one of the most intimidating defensive structures in the world.

In English we use the world Kremlin to refer to the one in Moscow, and to the Russian government as a metonym. But plenty of towns and cities have kremlins. It’s a bit of a shock to the senses the first time you turn the page in your guidebook to see “this town has a beautiful little kremlin”. It just means a citadel, a fortified place.

The Moscow Kremlin offers up many mental images. The idea that you can hand over £8.75 and just stroll in is ludicrous. How many secrets, how many horrors, does this place hold? It’s not quite Dark Tourism but “going into the Kremlin” doesn’t taste of light and magic.

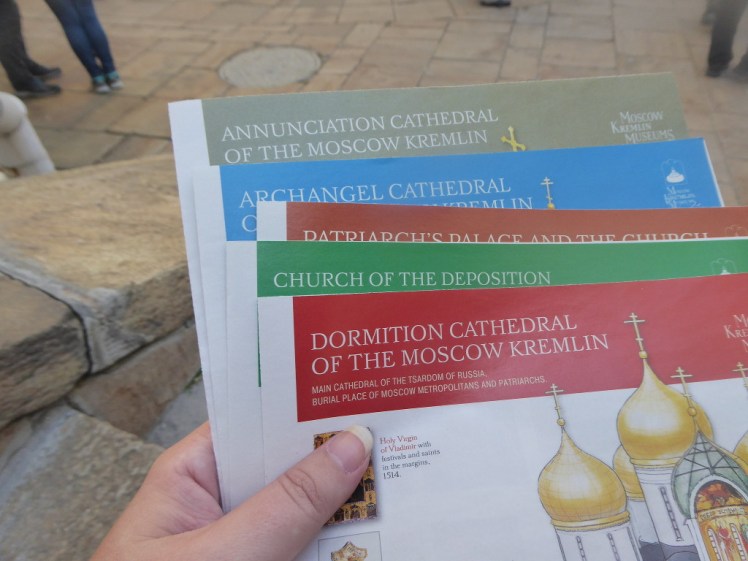

My ticket allowed me general admission to the public areas: the squares, provided I kept to the crossings, the gardens, the archaeological dig and the cathedrals. There are five, although the Church of the Deposition of the Robe is definitely only a church, and a small one at that, and the Patriarch’s Palace seems neither cathedral nor palace but a museum up an unlabelled number of stairs.

I wish you were allowed to take photos inside the cathedrals. There isn’t an inch of space on the walls or the ceiling that hasn’t been painted, gilded or frescoed. It’s a riot of colour, although dimly lit by small windows and a lot of slender candles. I have thoughts on the Russian Orthodox Church which you’ll see when I get to Ekaterinburg but these churches make quite the contrast with, say, Winchester Cathedral, which is very light, bright and white, partly because during the English Civil War all the stained glass was smashed and the windows are now all clear except the big western one. I think that’s a fair comparison: Kremlin cathedrals vs Winchester. Winchester was England’s capital and that cathedral was used for coronations and royal weddings and burials of kings and bishops, just like the Kremlin’s cathedrals. Ivan the Terrible was crowned in the Dormition Cathedral and buried, along with pretty much all pre-Peter the Great Tsars, in the Archangel Cathedral. As an aside, I like Ivan the Terrible. “Terrible” in Russian was a word that was actually closer to the English “Awesome”, in the sense of a storm at sea or a tornado rather than something really good. I like to think of Ivan as a tremendous force of nature. Of course, he did do some terrible things but he also built (not personally, he was Tsar!) St Basil’s Cathedral and carried (yes, personally this time) St Basil’s coffin.

So while modern day Winchester and Moscow aren’t comparable, their cathedrals are and they’re startlingly different. The leaflets you pick up in the porch of each church give pictures but they don’t do justice to the colour and the madness of the interior of these cathedrals.

You can’t go in all the Kremlin buildings. Some are museums where you need an extra ticket: see the Armoury Chambers. A lot of them are government or military buildings. The President’s Residence is here, as is his office although Putin has a mansion-slash-palace in the suburbs that he mostly works from to avoid Moscow traffic. Living within the Kremlin would achieve this also, I feel. On occasions when he needs to come to the a Kremlin, he arrives by helicopter. Must be nice being one of the scariest presidents in the world.

Behind the cathedrals are two of the largest artefacts in the world: a bell too big to ring and a cannon(technically a mortar) too big to fire. These are called the Tsar Bell and the Tsar Cannon. The bell weighs 200 tons, give or take the tiny 11 ton chip broken off it. In context, the heaviest bell able to ring is 115 tons and the biggest bell ever cast in the UK is just 16 tons; Great Paul in St Paul’s Cathedral which is also unable to be rung, because the chiming mechanism is broken. Our famous and beloved Big Ben is only 14 tons. As for the cannon, each ball weighs 1 ton. You can’t load them.

On your way across the square to the Spasskaya Tower, the Saviour’s Gate which functions as the main tourist exit when there isn’t an international military tattoo festival parked right outside, there are some shady gardens and even a rose garden with a water feature. I’d never pictured somewhere as intimidating as the Kremlin having a rose garden.

The day I was there, there was an international military tattoo festival parked outside so the Spasskaya Tower was closed. How to get out? All the signs are pointing to the closed tower. There are guards around but they’re all in the middle of the square watching that no one leaves the zebra crossings. They’re hard to get close enough to speak to and they’re Kremlin guards – scary people who probably don’t speak English. I’d said how illicit and transgressive it feels to go into the Kremlin. It amplifies when you realise you don’t know how to leave. I’m in the Kremlin and I can’t get out. I’m sure many people throughout history have experienced the same feeling. Suddenly the Kremlin feels very serious and very heavy. But there must be a way out. They can’t just corral tourists in here in the morning and then hold them prisoner. Someone would have noticed.

You leave via either the Borovitskaya Tower where the Armoury Chamber visitors enter or back through the Trinity Gate Tower. Some signs would be nice, Mr Putin.

And so I returned to the free world, to seek a drink, for mine had spilled and tried to kill my cameras and my guidebook. I’d survived my brief incarceration but now I had a battle with dehydration, which you don’t need to hear about.

Next time: I finish off my tales of Moscow, ready to head north to St Petersburg.

2 thoughts on “The day I was incarcerated in the Kremlin”