If you read my Chernobyl part 1 blog, you’ll know a little about the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone and its background. If you didn’t, go & read it before you carry on with this one.

Short primer: 32 years ago, its nuclear reactor exploded. Consequences were as bad as you might expect. Tourists can now go and look at it.

Our group was one of five minibuses setting off from Kyiv at 8am – two English-speaking minibuses, one Russian and two unidentified. By the end of the day, I’d seen twelve minibuses crammed into the same little lane and November is very low tourist season, which should give you an idea of how many tourists go to Chernobyl every day.

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is about 60 miles from Kyiv. We covered basic safety rules (long sleeves, closed shoes, no smoking, no alcohol or drugs, no running off, no touching the ground, no eating, don’t take the stray dogs home) and then watched a documentary the rest of the way, which contained an absolute wealth of new details.

We got to the first checkpoint. Here, we were warned again: no photos of the checkpoint or the guards, don’t try to cross and then left to our own devices for a time while important but tedious paperwork was filled in. Then we were lined up in list order and had our passports inspected by a border guard. Only then could we pass through the turnstile and then we had time to use the “last civilised restroom” of the day – for a slightly twisted definition of “civilised”, as far as I was concerned – while the minibus crossed the border. Here we were given Geiger counters, those of us who’d requested them and obviously I measured and write down everything. Radiation levels at the checkpoint were 0.17 microsieverts per hour. Average baseline level in Ukraine is 0.3, so this was much lower than average.

So now we were in the radiation zone – and it pretty much looks like what we’d been seeing ever since we left Kyiv behind. It’s a big patch of nothing, which is why the power plant was built there in the first place. The roads are a bit crumbly but they’re not great outside the zone either. Ok, there are some bridges that are now single-lane because the other lane hasn’t been maintained and is now unusable and yes, there are potholes but the roads aren’t so bad.

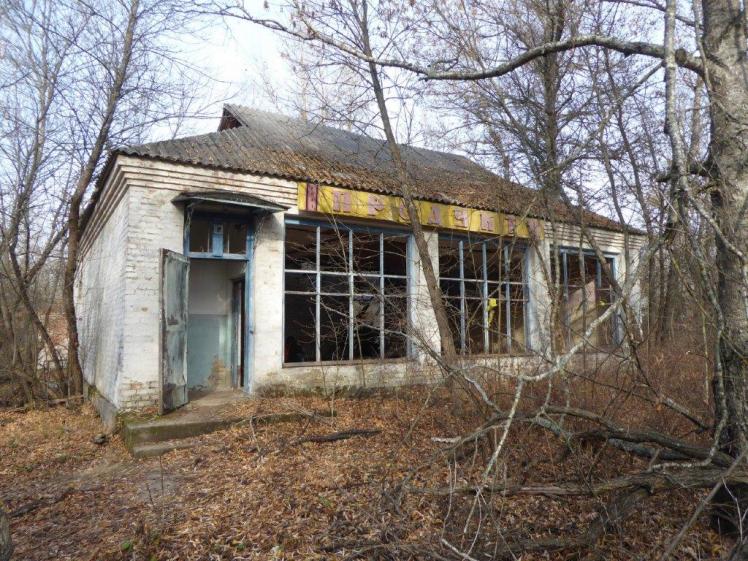

Our first stop was at Zalissya, the remains of a village not too from the edge of the 30km zone. It’s abandoned but it wasn’t too badly hit by the radiation. This was the only place where we were allowed to go into buildings. We went into a hospital that’s considerably smaller than my house, the remains of a grocery store and a house formerly lived in by a pre-teen girl called Yulya. The floors have been ripped up – they haven’t collapsed over time, they were deliberately torn up by looters hoping to find valuables stashed underneath. Gaping holes in the walls are where those same looters have torn out the copper wiring. Apparently the reason for the newspapers all over the floor is that newspapers are worthless and got left behind – but there were so many of them. Even my dad couldn’t accumulate that many newspapers on the floor in under a month. There has to be more to the newspapers than just “not valuable enough to steal”.

As for Yulya’s house, we know she lived there because some of her school books survived. Her family had a holiday to Crimea a couple of years earlier, judging by a surviving calendar with a picture of Crimea on it – that means they were doing pretty well, by Soviet standards.

Next up, after the less intense checkpoint at Leliv, where we didn’t get our passports checked, we stopped at Kopachi. If you’ve seen pictures of abandoned dolls and crumbly kids’ beds, it would have been in the kindergarten here. This one was a bit more delicate – it’s within the 10km zone, it’s almost as close to the power plant as Pripyat is and this place was saved by the liquidators. That means that the buildings were washed with soap and water to remove the radiation. Stick with me. Alpha & beta particles are big and heavy and cling to things. They’re tangible. You can wash them off. Gamma radiation, being a wave that just wafts its way wherever it wants, is not washable. But of course, all the soapy radioactive water dripped down the walls and soaked into the soil around the base of the houses so a few feet from the walls, the ground gets very radioactive. And the trees that have sprung up in the last 32 years are brilliant radiation sponges, which means they’re very radioactive too, especially near the roots. In Kopachi, you try to stand on nothing but concrete, which doesn’t soak up radioactive particles. You touch nothing, even with your feet if possible.

And yes, we went into the kindergarten. Not an original shot here, to quote Tom Scott. Tourists taking photos of dolls and beds. This is the Chernobyl people came to see.

The big stop on this trip was in Pripyat, the city built to house the power plant workers. This was a place where the average age was 26, where people were young and educated and qualified – “best place for best people” said the Soviet propaganda. And of course, as well as the workers there were the people who had to run the city – the spouses and kids, the people who worked at the Palace of Culture and the cinema and the pool and the supermarket (the first supermarket in the Soviet Union). This city was built in 1970 and home to 50,000 people. It’s about two miles from Reactor 4. From the right angle, you can see it. From the higher floors of apartment blocks you can see it.

We were dropped next to the port-cafe, where people arrived on the slow boat from Kyiv and then walked down to the central square, past the remains of a thriving young city, past some of the last Soviet landmarks in Ukraine – following a revolution in 2013-2014, all the Soviet monuments were torn down. You won’t find many, if any, Lenin statues in Ukraine. You won’t find hammer-and-sickle decorations or big red stars. But some of them survive in Pripyat.

The accident happened on Friday night. Pripyat was evacuated on Sunday afternoon, the inhabitants told they’d be away three days. Liquidators lived here while they cleaned up the Exclusion Zone. The swimming pool was still in use well into the 1990s, apparently safe from alpha & beta radiation from being inside and I guess no more dangerous from gamma radiation than just existing in the city. It’s a ghost town now; the liquidators moved out long ago and the inhabitants never came back. It’s too crumbly to come back to. It can’t be all that long until it’s too crumbly to bring tourists to.

Our guides had a book of photos of Pripyat in the 70s and 80s. It was a model town, “Soviet paradise” so it was well-documented. Our guides would hold up the photos so we could see before-and-after right there in front of us.

The most exciting bit came next. Lunch. This was exciting because we had it at the canteen at Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The very same one that exploded. The canteen is down the other end, well away from Reactor 4 and it feeds the workers who are dismantling and decommissioning the place and most of the tourists. We had to go through our first radiation control before we were allowed in – a kind of green metal frame where you put your hands and feet on detection panels and it looks at you and puts on one of three lights, depending on whether you’re uncontaminated enough to let through. I passed with flying colours.

This is lunch at ChNPP.

After lunch we went to see Reactor 4. For security, you’re not allowed to take photos of the power plant anywhere except the reactor at a particular angle. No photos of the defences or the new admin building. Nuclear secrets alert: the defences are a high fence topped with razor wire and the new admin building is a two-storey portacabin. This was the highlight for me. I’ve watched the New Safe Confinement being built on Wikipedia for a couple of years so it was quite exciting to see it finished.

Immediately after the accident, they built a cover, called the Sarcophagus, assembled in haste by helicopter. It wasn’t brilliant, it was leaky and not well-built but it did the job, more or less. The New Safe Confinement is a huge steel arch, triple-layered, designed to keep everything in and everything out, built to fit perfectly over the remains and built a couple of hundred yards away to reduce radiation exposure. It was slid into place on a set of rails, making it the largest movable (land-based) object on Earth. Underneath, the NSC is filled with robot arms that will have the wreckage dismantled by 2065, although the arch is meant to keep everything contained for a hundred years.

By now, we were all getting tired. It had been a long day and the three Luxembourgish bankers I was hanging around with were bored and hungry and not particularly impressed. But we still had two stops.

The first was Radar Duga-1, a Secret Soviet Military Installation, hidden in the forest and disguised on maps as an abandoned Soviet kids’ camp. It was an over-the-horizon radar array, which could detect US missile launches long before they hit, although probably not long enough to do much about it. It never worked and it gave out a signal that blocked radios for miles around and earned it the nickname The Russian Woodpecker and it deserved more interest than we could give it. It’s very cool to go to a Secret Soviet Military Installation – but it looked like a gigantic, 150m high fence and we were cold and tired.

By the time we reached Chernobyl City, it was pretty dark. We stopped at a display of robots – automated machines that helped clear the disaster. Some of these are extremely radioactive – one of them worked on the roof of the power plant, clearing away chunks of burning graphite before the Sarcophagus could be constructed. And finally, we stopped at the monument to Those Who Saved the World – the people who were first on the scene, the firefighters, the doctors, the engineers etc. The people who put out the fire and prevented the second explosion, the people who mostly died very quickly of radiation sickness. It’s right outside Chernobyl fire station and is the centrepiece of the annual… well, celebration is the wrong word, but the annual remembrance, when fire engines from miles around drive around the Exclusion Zone and through the roads surrounding the power plant, with their sirens and lights going, to commemorate the firefighters who walked into a nuclear explosion.

The only thing left to do was pass the last radiation control, back at CP Dytiatky. This one is more sensitive but if you’ve walked through radioactive dust, maybe you can pass by standing on the plates with only one foot. I didn’t do that. I didn’t need to. I passed just fine. And when the guides read my Geiger counter, it turned out I’d been exposed to 0.004 millisieverts of radiation. That’s about forty bananas. The Banana Equivalent Dose is a thing – bananas are naturally radioactive. A damaging dose is 1 sievert – that’s a million milliseiverts, so you can see how little radiation I absorbed in that day. Even a tour guide going every single day wouldn’t get anywhere near that in a year and our guide had 0.006 millisieverts, because she deliberately sought out the hotspots to show us. That dose every day for a year comes to 2.19 millisieverts, and they don’t go there every day.

Then there was more paperwork to show we’d left, while we sat in the minibus an complained because we couldn’t figure out where the guides had gone.

I don’t want to say it was a great day. It wasn’t. But it was a very interesting and very educational day and I’m glad I went. I’ve seen photos of people who’ve been multiple times, people who saw the sarcophagus and then saw Reactor 4 again when it was covered by the NSC. I’d like to go again when things look different but there’s not going to be much significant change for a long time. Maybe when I’m in my 80s I’ll go back and see how much of the power plant has actually been dismantled and decommissioned.

In the meantime, I’ve had a lot to read up on – background reading on everything we saw in the documentary and everything we were told during the day and everything to do with nuclear physics, because all I really gathered was that iodine-131 was scattered over the zone. And now I know a bit more about that.